Introduction

As designers, we always hear how important it is that our deliverables ensure user engagement and interaction, elicit responses and delight. This focus on engagement is pervasive, from how successful UX is measured to auto-play, and gamification – design elements meant to get users involved with their devices. But what is the psychological impact of ubiquitous tech and how are users pushing back? How can UX designers begin reintroducing the humane in human-centered design?

The Problem

Discussion of the negative mental impact of technology is nothing new and has developed significantly over the last few years. From anxiety and depression caused by social media to gaming addiction, the psychological cost of technology can no longer be ignored.

Various theories from cognitive psychology have been adapted for use in UX, which has increased the importance and scale of user engagement. Applying these learnings to design has often resulted in genuinely addictive and omnipresent experiences. I will discuss two theories I believe are especially relevant given their contemporary and pervasive use:

- Nudge Theory

Thaler and Cass introduced this concept in their 2008 book of the same name. It works subtly, by unconsciously guiding decision-making towards choices that are broadly in our self-interest. An example would be organ donation where users are opted-in by default. Conscious effort is required to opt-out, so we are nudged in the right direction, remaining a donor. Nudging is used extensively in the digital realm to lead users to take specific actions, often unconsciously. We may receive time or location-specific push notifications if our fitness tracker wants us to take a few more steps during our lunch break. Or, if we want users to donate $20 to an online campaign, we may make that the default input in the value field, requiring effort to change this number. - The Principle of Variable Rewards

Pioneered by B.F. Skinner, the principle is that if you want to ensure an action keeps happening, make the reward for that action vary. For example, if we’re going to keep going to the gym, we should establish a surprising reward pattern – we might get a chocolate bar for our first three visits, nothing the fourth visit, and a new pair of trainers on the fifth. Skinner found that variable rewards ensured the most instances of an action reoccurring, and it also led to behavior that was “hard to extinguish.” In other words, even after rewards stop, we may still head to the gym. In UX, an example of this is the “pull to refresh” feature on Twitter or Instagram. Like a slot machine, when we pull, we never know what the reward will be: perhaps a video from our favorite artist, a news-worthy tweet, or new likes on that picture we just posted.

Together, the application of these theories in UX is just a small example of how technology has been holding our psyche hostage over engagement. It’s no surprise that the growing backlash is calling for silence.

The Backlash

As tech companies are beginning to face up to the ‘always-on’ reality they have created, they are also responding to users demanding more control over how technology drives our lives. In 2018, both Apple and Google came out with apps designed to limit our screen time and provide data on how long we spend looking at our phones. Digital detoxes are on the rise, as are organizations aimed at countering unhealthy design practices, such as Mindful Technology and the Center for Humane Technology.

Perhaps the most significant illustration of a need for silence is the resurgence of physical products that give users more control over their usage. The Light Phone, introduced a few years ago on Kickstarter, only has one function, making calls; while Sony announced at the end of 2018 that it was bringing back it’s PlayStation Classic console (Fjord Trends 2019 Report). It’s becoming increasingly clear that:

“The values users seek from the products, services and organizations we choose to interact with are shifting. Where once we celebrated novelty, excitement and instant gratification, we now reject organizations that shout to get our attention.”

(Fjord Trends 2019 Report, p. 11).

The Way Forward

Adapting to changing user behaviors will need to occur in two major areas:

- In how businesses measure and value the success of their UX practices, and;

- In how we design for the least amount of disruption possible.

If companies remain committed to KPIs that prioritize engagement, then accurate measures of success with users may be overlooked entirely – perhaps the best engagement outcome is none at all. Companies will need to develop or prioritize other metrics that point to real user satisfaction. For example, the frequency of interactions may now be less important than how long a user has an app without deleting it.

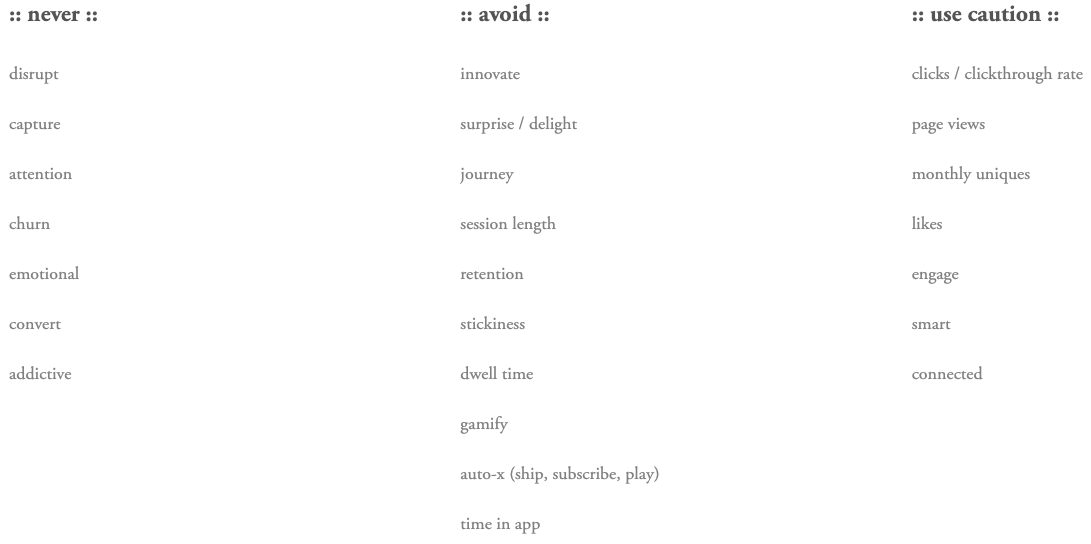

As UX designers we will need to re-think products and interfaces to be as minimally invasive as possible. This is especially important as voice UX begins to grow, as it is easier to avoid looking at screens than it is to tune out unwanted sounds. Humane, thoughtful and ethical considerations should be prioritized in favor of designs that focus on engagement, producing stressful and often shallow relationships with technology. This means avoiding the use of what Mindful Technology has coined ‘anti-patterns’ and ‘coded language’ that perpetuate harmful design practices, such as:

Conclusion

As the negative side-effects of technology threaten to overwhelm us, actively choosing to disengage with our digital products may be one of the few ways we feel like we still have control. Companies that do not support users in this goal risk losing their trust. Designers have a responsibility to create interfaces that make it as easy as possible for users to chose the intensity of engagement they would like to have, while businesses need to recognize and champion measures that lead to less-invasive products. Those who can successfully support their users in having an effective but limited digital experience will stand out.

“Rather than being big, bold and noisy, to avoid being ignored – or worse, abandoned – organizations need to pipe down.”

(Fjord Trends 2019 Report, p. 12).

References

- https://trends.fjordnet.com/Trends_2019_download.pdf

- https://www.mindfultechnology.com

- https://cacm.acm.org/magazines/2018/7/229029-digital-nudging/fulltext

- https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2015/aug/07/nudge-theory-smart-gadgets-silicon-valley

- http://humanetech.com/

- https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/brain-wise/201311/use-unpredictable-rewards-keep-behavior-going

- https://www.1843magazine.com/features/the-scientists-who-make-apps-addictive

- https://uxplanet.org/the-hidden-power-of-reward-systems-in-design-78e2dd7b6bf6

- https://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/analysis-and-features/nudge-theory-richard-thaler-meaning-explanation-what-is-it-nobel-economics-prize-winner-2017-a7990461.html

- https://www.bcg.com/en-us/publications/2017/people-organization-operations-persuasive-power-digital-nudge.aspx

- https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/charliewarzel/tech-addiction-rehab-online-detox