Designing for difficult contexts—for situations where a product or interface is serving users in heightened emotional states or positions of physical or sociopolitical vulnerability—presents particular challenges to the designer. Literature on the issue stresses the importance of ensuring that general usability principles are part of the design process (e.g., functionality, flow, aesthetics, task success, and user satisfaction), as well as working with additional measures and guidelines based in previous research and user feedback (e.g., pleasure, meaning, and measures in alignment with care-expert best practices) to guide designing for these special contextual environments.

Although user experience is always central to good design, for projects falling into this category it is of crucial importance. Designing for difficult contexts requires that the designer be sensitive to user perspective in order to create designs that facilitate task success—because the design may impact significant life conditions, such as user ability to navigate needed healthcare resources or basic food and water. Attending to design’s role in functionality as well as design’s contribution to user experiences of pleasure and empowerment can both help users to utilize tools effectively and impact their mental and emotional well-being. Design can help empower in moments of powerlessness.

Real-world examples of these types of design projects demonstrate principles that can help designers work toward better, more pleasurable, and more empowering designs. Four approaches that designers can incorporate that are particularly useful to these contexts include: (1) empathy and attentiveness to the emotional context of users; (2) sensitivity to the physical and sociopolitical vulnerabilities and constraints of users; (3) incorporating into the design process expert perspectives from those who support these populations in other areas; and (4) contributing to the comfort and empowerment of users through generating pleasurable user experiences.

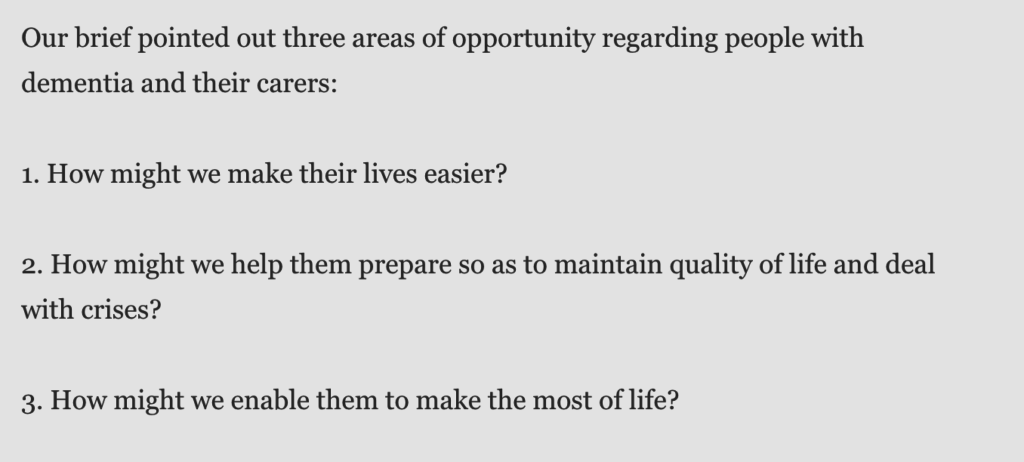

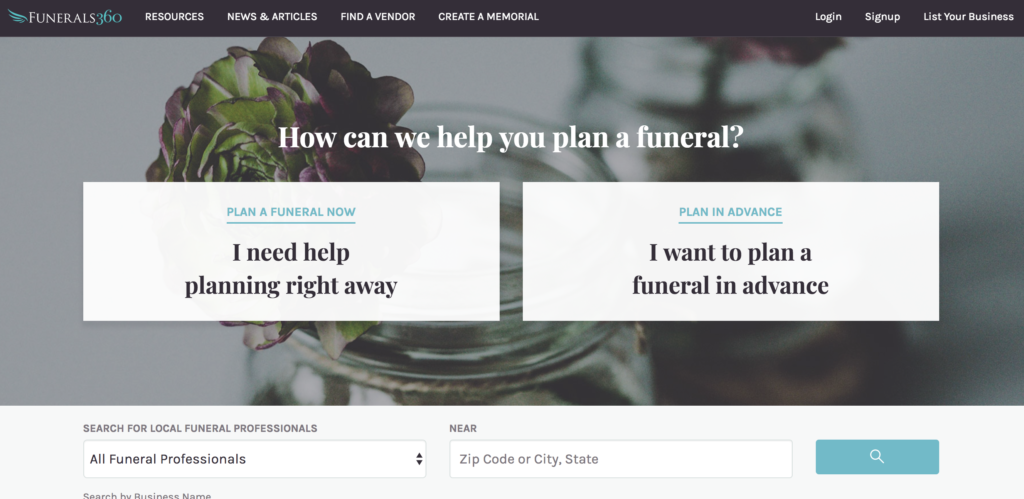

1) Centering Empathy

Centering empathy means attending to special populations’ probable experiences and points of view—trying to understand the kinds of feelings and past experiences that might shape their experience of a design even before they have encountered it. For example, designers creating funeral planning apps need to select colors and imagery appropriate to their users’ emotional state (see image from Funeral360 below); designers creating apps for coping with dementia need to keep in mind that they are not only designing tools that facilitate specific tasks, but also that facilitate broader support for their life conditions (as demonstrated in design brief from a UK Health Service design challenge call for proposals below):

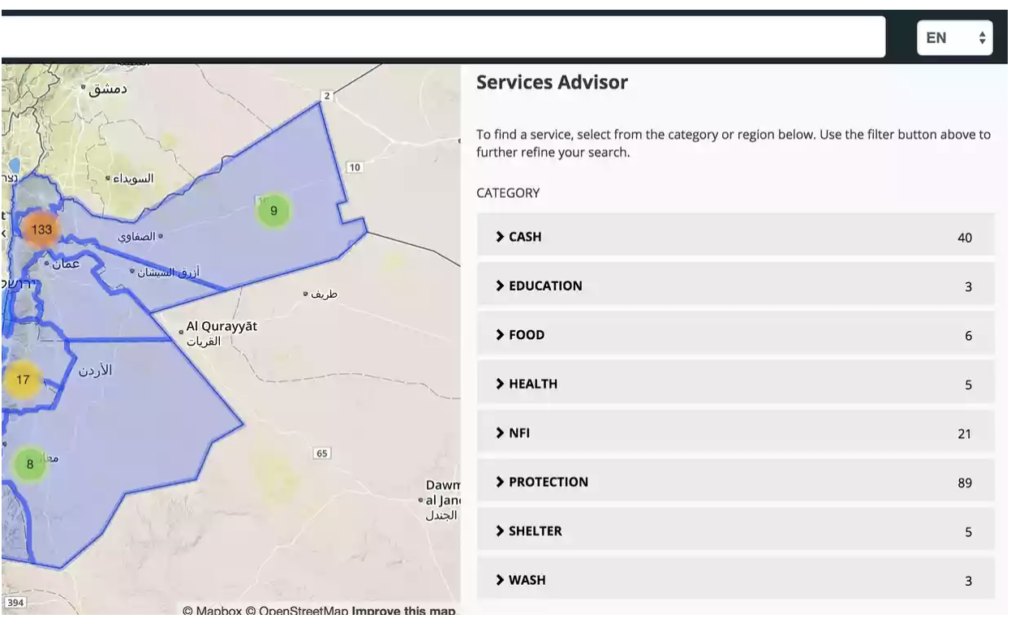

2) Recognizing Physical & Sociopolitical Vulnerabilities

Vulnerabilities related to user contexts, physical, socio-political, or otherwise, also need to inform the design process for these contexts. For example, though apps have the potential to play a useful role in refugee/asylum situations because many persons in migration carry cellphones with them, this context requires special sensitivity—particularly to issues of vulnerability to environmental and sociopolitical factors, limited data or cell-service access, and the need to protect identity information. The Red Cross’s Refugee Buddy app and UNHCR Services Advisor app are two examples that incorporate this design sensitivity, as they are designed to help direct refugees to needed services without requiring identifying information:

3) Incorporating Expert Perspectives

In order to be sensitive to the specific needs of users who would utilize the app/product/interface, it’s imperative that designers work with experts in the relevant fields they are designing for who can provide best-practice recommendations to support these populations. In design for physical or mental health-related services/tools, this may require input and testing on usability from physicians and care-giver experts, as well as target users, in order to reach successful and appropriate designs. For example, the designers at Mad-Pow studio have developed guideline recommendations for incorporating expert medical advice into multiple design stages of mental health apps and websites:

4) Acknowledging the Role of Design in Pleasure, Empowerment, and Meaning-Making

It is widely acknowledged by design theorists that the experience of pleasure has a key role to play in design. In his book, The Design of Everyday Things, influential usability expert Don Norman underscores the interrelationships between emotion and design, citing the importance of pleasure, saying, “the total experience of a product covers much more than its usability: aesthetics, pleasure, and fun play critically important roles” (p. xiii). Pleasure as a factor of user experience has a particularly significant role in designing for difficult contexts. Users are likely to be coming from experiences that involve pain, sadness, loss, disempowerment, and other highly stressful, highly negative experiences; designs that take into account both meeting users’ task-based needs and also providing a realm in which they may be able to experience satisfaction, hope, beauty, escape, or pleasure offer a very important resource to the human beings going through these experiences. Pleasure may or may not be directly articulated in the design specifications for these projects, but it is a design goal with the potential to make tremendous impact on the lives of people.

Conclusion

Design for difficult contexts presents special design challenges. Looking to successful previous project examples for models, such as in the four categories of examples outlined above, can help designers who are new to design for difficult contexts navigate the specific needs of these projects. By centering empathy, recognizing that users are likely to be coming to the website, app, or other product already in a heightened emotional state or in a condition of pain, stress, sadness, and/or fear, by attending to the physical and sociopolitical vulnerabilities of users, by incorporating input from care experts knowledgable about the users’ context and needs, and by attending to the crucial importance of designs that can contribute to pleasure and empowerment, designers can be well-prepared to meet these challenges. Ultimately, good design in difficult contexts can help people make meaning when other aspects of experience may feel meaningless, feel empowered when they may feel powerless, feel pleasure in the face of pain. Good design in difficult contexts can be a form of care for others.

Norman, D. A. (1990). The design of everyday things. New York: Doubleday.