Invisible disabilities

In learning more about accessibility in design, I was interested in looking at an invisible disability, one that may not be as apparent as a physical one but can also be disabling. It can greatly affect one’s daily life and how they navigate the world performing normal activities that someone who is not cognitively impaired may take for granted.

Reading is a fun diversion, whether it’s a riveting novel or an interesting blog post or a funny tweet. It becomes a challenge when you are sleep-deprived or in a noisy environment and it’s hard to concentrate. This simple activity poses an even greater challenge for people with cognitive impairments that affect their ability to read.

In an article on ReadingRockets.org, it states that researchers have identified three kinds of developmental reading disabilities that often overlap but that can be separate and distinct:

(1) phonological deficit

(2) processing speed/orthographic processing deficit

(3) comprehension deficit

Source: ReadingRockets.org

It went on to explain that children suffering from reading difficulties are called “reading impaired.” Some poor readers can decode words better than they can comprehend the meanings of passages. These poor readers are distinguished from dyslexic poor readers because they can read words accurately and quickly and they can spell.

Conversely, good readers are phonemically aware, resulting in their ability to apply this skill in a quick and fluent manner, plus possess strong vocabularies and syntactical and grammatical skills.

According to the LD Online website, 5-15% of Americans — 14.5 to 43.5 million children and adults — have dyslexia, a learning disability that makes it difficult to read, write, and spell, no matter how hard the person tries or how intelligent he or she is.

Assistive technology

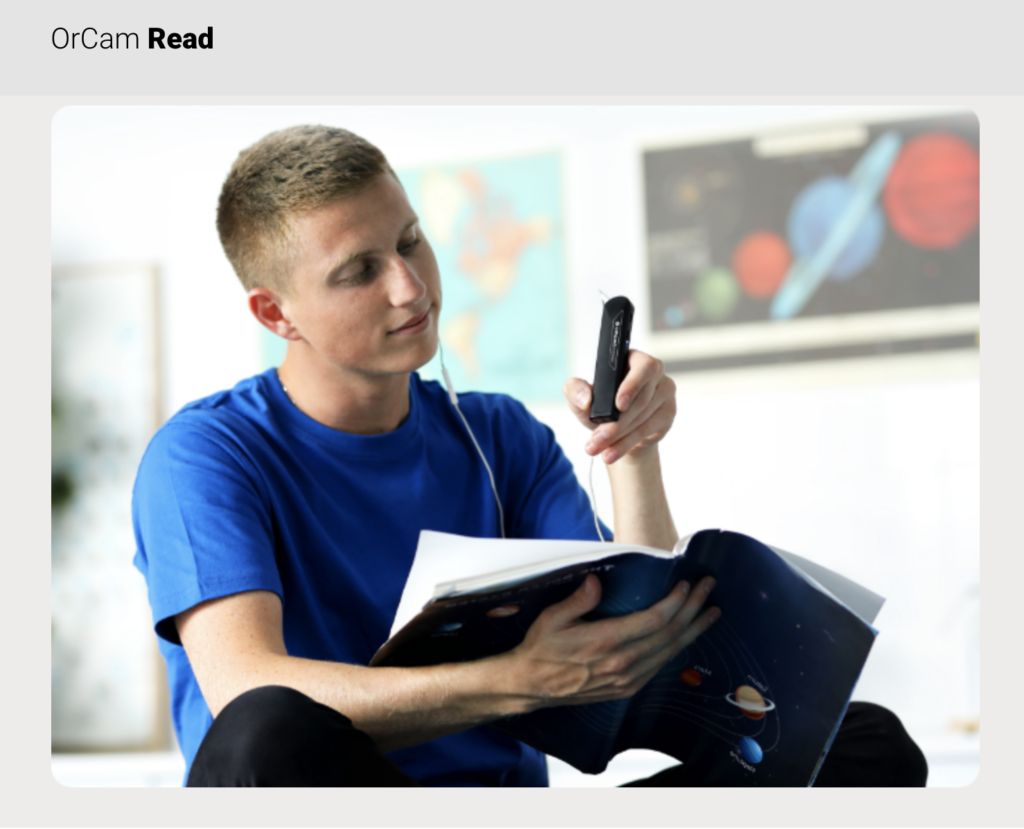

After doing research into technologies that help with reading disorders, I discovered the OrCam Read device, which helps people with dyslexia or other cognitive disabilities, as well as people suffering from low vision or reading fatigue.

It is a sleek handheld device, small and portable. Users point and click at a digital screen or piece of paper, textbook or magazine. They can also control it through voice commands — the “Smart Reading” feature lets users ask it to read specific areas like the headlines only or a certain portion of the full text. Their audience includes those who consume large amounts of text on a daily basis, such as students and professionals. This technology can be used in any environment, including low-light, and doesn’t require internet connectivity, which makes it easy to use anywhere.

Disability blogger Chloe Tear wrote a review of the device in 2020 —

It fills a massive gap in the market for a wide range of people and it is able to aid independence in many areas of daily life. I believe this product has potential to massively help my own independence. The simple things like going to a shop and stocking up on essentials, that most people probably don’t give a second thought, would be made easier.

While it does sound like a fantastic technology that can benefit many, one major downside is the nearly $1,990 price point, making it less accessible, leaving a large segment of the population out of getting something that could greatly improve their reading experience. Perhaps this could be something made available through schools or libraries for greater access.

The social model of disability

I would place reading disorders like dyslexia under the social model of disability. The way the typical learning environment is structured prevents students with dyslexia from fully participating in classroom activities. Reading out loud is something we have to do as young children first learning to read in grade school and this causes anxiety for those who can’t read at the same speed as other students, which causes shame and frustration. Classrooms should be more conducive to students with different learning abilities so they can thrive too.