Introduction

Assistive technologies have revolutionized the way individuals with disabilities navigate the world, granting greater independence and usability for everyday activities. As one of the most widely used navigation tools, Google Maps has taken meaningful steps to improve accessibility through features like wheelchair-accessible routes and voice-guided navigation for blind or visually impaired individuals. To understand the effectiveness of these features, I analyze them using the social and medical models of disability—frameworks that offer unique perspectives on how technology addresses barriers and individual needs.

Wheelchair-Accessible Routes

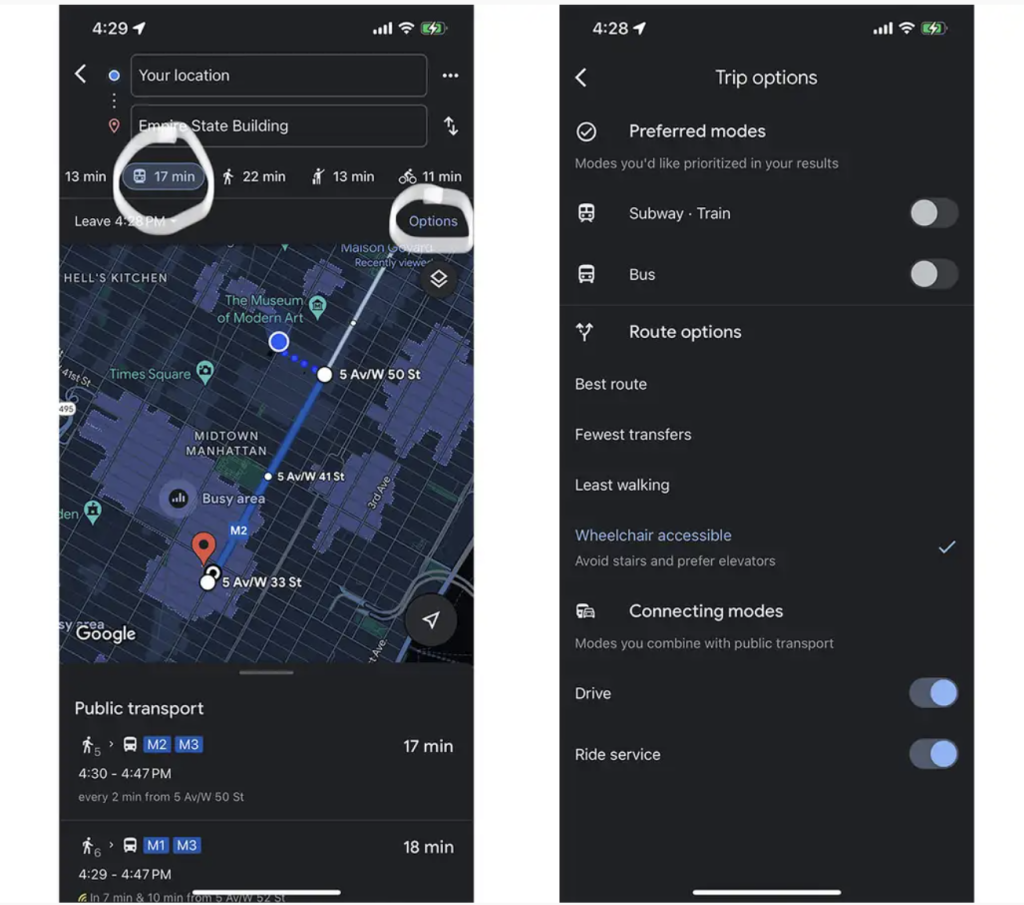

The wheelchair-accessible route feature in Google Maps allows users to filter navigation by finding routes with elevators, ramps, and step-free access. This functionality is a significant example of tackling societal barriers that prevent mobility.

From the perspective of the social model of disability, which views disability as a construct of societal and environmental barriers, Google Maps makes a tangible effort to address these issues. Enabling users to quickly identify routes based on accessibility or avoiding inaccessible transit stations provides mobility-impaired individuals with more freedom and confidence in their navigation. Additionally, highlighting accessible entrances to buildings further removes environmental barriers that might otherwise limit participation in public spaces.

However, the feature exhibits shortcomings through the lens of the medical model of disability, which emphasizes addressing the impairment itself. Google Maps applies a broad, generalized notion of accessibility, lumping all users into the same category of “wheelchair users.” This approach often overlooks specific needs: for example, a user with crutches, a walker, or a service animal might have distinct challenges not addressed by the generic “accessible” route. A potential improvement would be to enable customizable filters for users with varying mobility needs, allowing them to select routes that accommodate their specific requirements.

Voice-Guided Navigation

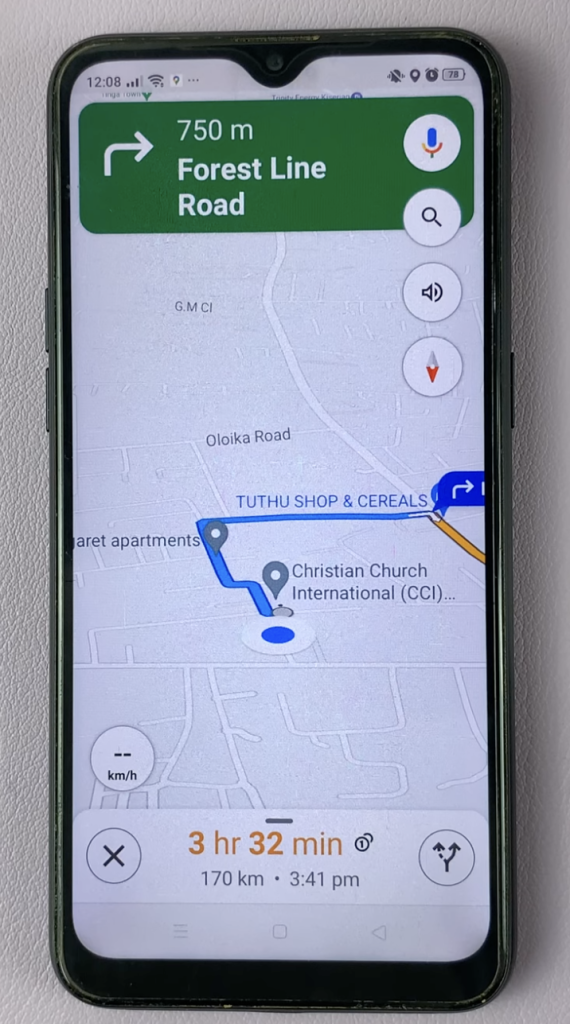

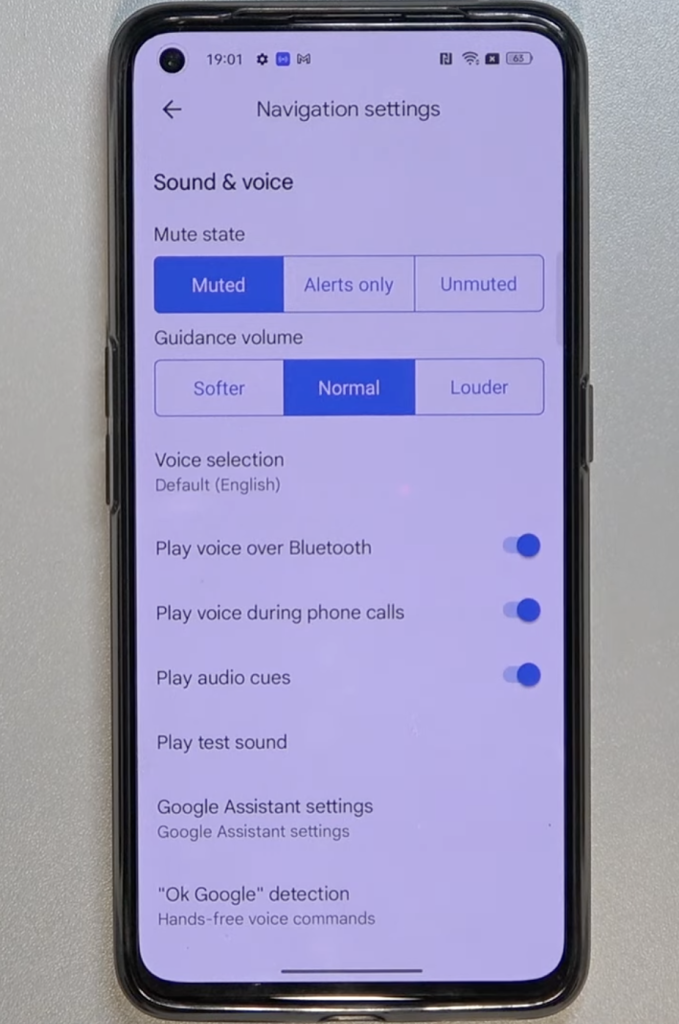

For users who have visual impairments, voice-guided navigation provides audible step-by-step navigation features, such as announcing street names, turns, and alerts for busy intersections. This feature aligns closely with the medical model by addressing functional impairments through technology, offering users greater independence and safety during outdoor travel.

While voice-guided navigation provides a practical solution, its evaluation through the social model reveals areas for improvement. One limitation arises due to the dependency on stable internet connectivity—a persistent societal barrier in low-connection areas. Another issue is the lack of multimodal feedback mechanisms. Currently, the app relies solely on auditory cues, excluding users with dual sensory impairments (for example, individuals who are both blind and deaf). Adding vibration-based feedback or tangible cues could provide an additional layer of inclusive communication, benefiting a wider range of users. Such innovations could create a more robust solution for diverse accessibility needs.

Disability Etiquette in Technology Design

Effective accessibility design considers not just functionality, but also the language and etiquette used to describe users and their needs. Google Maps should ensure that it centers users as individuals rather than defining them by their disability. For instance, referring to users as “individuals with visual impairments” instead of “the visually impaired” emphasizes person-first language, respecting personhood rather than focusing on the disability.

Conclusion

Google Maps demonstrates its dedication to accessibility with features like wheelchair-accessible routes and voice-guided navigation. However, analysis through the social and medical models of disability reveals gaps that could be addressed to better serve diverse user groups. Customizable route filtering, integration of multimodal haptic feedback, and reduced reliance on internet connectivity could take Google Maps from a good accessibility tool to an exceptional one.

References

www.youtube.com/watch?v=-oWsAMwJ-ks

www.youtube.com/watch?v=gynI5hbl87Q

https://www.lifewire.com/how-to-use-google-maps-with-voice-guidance-4797412