The New York Public Library’s Picture Collection is a trove of over 1.5 million images, ranging from vintage postcards to historical photographs. Digitized as part of NYPL’s Digital Collections, these images serve as resources for artists, researchers, and educators. However, many of these digitized images lack essential features, particularly alternative text. Providing context is central to libraries and archives’ missions—and this absence represents a missed opportunity to both improve accessibility and offer a critical, reparative interpretation of these visual materials.

“The Pageant of America” collection, a case study for this assessment, was donated by Herbert Brook in the 1980s and originates from a eponymous landmark pictorial history series published by Yale University Press between 1925 and 1929. According to NYPL’s collection description, this series of images was heralded for legitimizing visual materials as scholarly sources. The series offered a richly illustrated narrative of U.S. history, and laid the groundwork for popular historical storytelling formats still in use today.

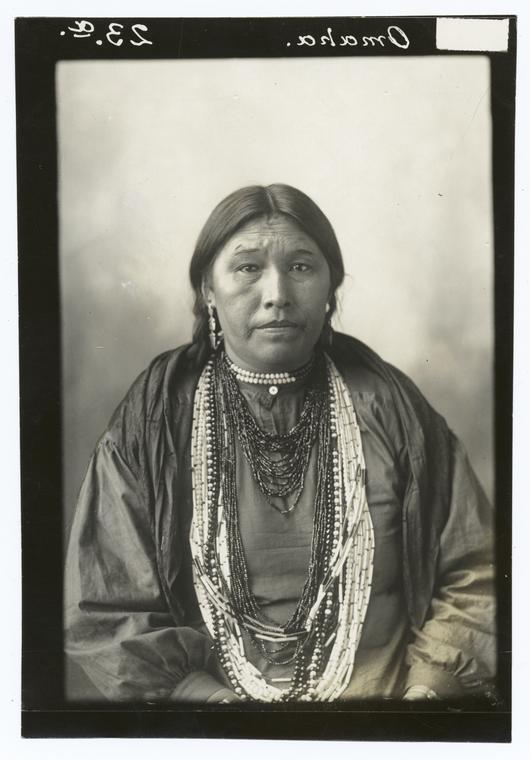

Of particular concern is the representation of settler colonization and Indigenous peoples, particularly the extractive, exploitative nature of these photographs. One instance—out of countless similar images—is an image titled “A full-blood Omaha Woman”. It could be argued that this is simply a reflection of respect de fonds, an archival principle which maintains the original context of the collection as it was inherited. However, in the vast majority of cases, images such as this lack meaningful alt text, and instead reiterate the dehumanization embedded in their titles as a grasp at checking off boxes for accessibility.

Descriptive practices are never neutral. When institutions like NYPL fail to invest in inclusive, reparative metadata, they not only miss an opportunity to deepen user engagement across abilities—they also perpetuate the structural exclusions these collections too often reflect.

As libraries and archives continue to digitize materials at scale, how might they move beyond surface-level accessibility and toward a model that genuinely interrogates the power dynamics embedded in the visual record?