Museums across New York City, the United States, and the world dedicate their resources to providing information to their patrons. To do this, museums have entered a world of digital collections and catalogs. These online resources are used by the casual viewer and a curious patron who has tumbled down a Reddit rabbit hole. These websites typically structure pages to be visually appealing, with various collection highlights featured on each webpage. However, for people with low vision or people who are blind, these images must be adequately accessible. Each image on a website, according to the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) standards, should have alternative text or “alt-text.” Unfortunately, this is not the case and continues to be a barrier for people with low vision or blindness.

The Cooper Hewitt Museum defines alternative text as “…a short visual description that provides a general sense of the content of an image. It is structured as a sentence fragment that indicates the most important content of the image; it is approximately fifteen words and contains no period at the end unless it is a complete sentence” (Cooper Hewitt). There are differing guidelines for how many words should be in an alternative text; for example, the Cooper Hewitt Museum recommends fifteen words max, while the Perkins Institute for the Blind suggests between one hundred and one hundred twenty-five characters.

There is a reason behind the short and sweet alt-text rule. I used what I have coined, “the email subject line rule,” which is exactly what it sounds like: alt text is a preview of what’s within the image. The alt-text is not an image description; an image description provides necessary detail regarding the materials, size, people, and colors within an image, even more so when discussing museum collections.

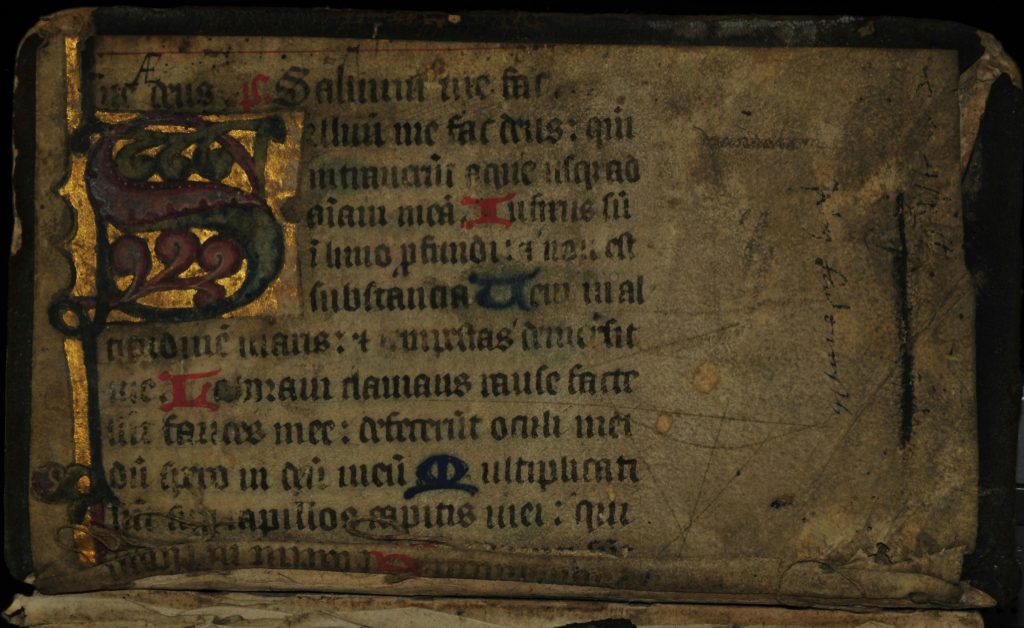

When evaluating The Morgan Library’s image alt-texts, of which there are none, I concluded that they were overlooked in favor of image descriptions. While these image descriptions were placed in paragraph form below the images, the alt-text was forgotten. When looking for a specific image with a screen reader or for someone with low vision, the alt-text will provide immediate information about the image. It will allow the user to move on from insignificant images.

My solution to this massive accessibility oversight from The Morgan Library is not cheap or quick. This project would require a complete overhaul of their website’s alt-text. Each image must be assessed by a team of privileged knowledge experts, meaning experts within a field or institution, who understand the jargon associated with their profession. These teams would have to move systematically through images, assess their significance as a collection piece, determine the relevance within the specific manuscript, and then determine how the image relates to the information within the manuscript. A project of this size takes time and staffing that, unfortunately, is usually put towards other grants and projects.

I hope that someone within The Morgan Library will understand that the large population is restricted from using the museum’s collection to the fullest extent. This kind of project requires time and money, which could be offset by grants, donations, and accounting for accessibility standards in the yearly budget. The Morgan Library must account for the population of people who use screen readers by updating their HTML standards and subsequent alt-text. I’m afraid that without these updates, The Morgan Library’s online accessibility standards will remain stuck in the dark ages.

Citations

Alternative text. WebAIM. (n.d.). https://webaim.org/techniques/alttext/

Carter Collection. Carter Collection | Amon Carter Museum of American Art. (n.d.). https://www.cartermuseum.org/carter-collection?page=2&art=1&archive=0

Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures. (n.d.). Accessible Manuscript Preparation: A Guide to Alt Text. University of Hamburg. https://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/publications/smc/accessible-manuscript-preparation-degruyter.html

Cooper Hewitt. (2022, March 2). Cooper Hewitt Guidelines for Image Description. Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum. https://www.cooperhewitt.org/cooper-hewitt-guidelines-for-image-description/

How to meet WCAG (quick reference). How to Meet WCAG (Quickref Reference). (n.d.). https://www.w3.org/WAI/WCAG22/quickref/?versions=2.1#principle1

Lewis, V. (2018, January 31). How to Write Alt Text Image Descriptions for the Visually Impaired. Veronica With Four Eyes. https://veroniiiica.com/how-to-write-alt-text-image-descriptions-visually-impaired/

Lewis, V. (2021, February 11). Seven Myths About Alt Text. Veronica With Four Eyes. https://veroniiiica.com/seven-myths-about-alt-text/

Perkins School for the Blind. (2024, August 15). Guide How to Write Alt Text and Image Descriptions for the Visually Impaired. Perkins. https://www.perkins.org/resource/how-write-alt-text-and-image-descriptions-visually-impaired/

Pierpont Morgan Library. MS H.3, fol. 1r.

Richardson, J. (2023, July 15). Making museum websites accessible: Adventures in alt text with the Amon Carter Museum of American Art. MuseumNext. https://www.museumnext.com/article/making-museum-websites-accessible-with-alt-text/