Apple Watch AssistiveTouch enables users to control their watch without touching the screen. Using built-in motion sensors, it detects subtle hand gestures, such as pinching or clenching, to navigate, select, and activate features. Designed for users with upper limb differences, it transforms wrist movement into a fully functional input method.

Wearable technology assumes a very specific type of user, someone who can tap small icons, swipe precisely, and use both hands comfortably. The Apple Watch, with its compact interface and touch-based navigation, is built around these expectations. AssistiveTouch challenges those assumptions by redefining how input can be detected. Rather than requiring direct contact with the screen, it interprets muscle movement as intent. This shift is subtle, but it represents a meaningful rethinking of interaction design in mainstream consumer technology.

What Assistive Touch Actually Does

AssistiveTouch allows users to:

- Pinch to move forward in a scanning interface

- Double pinch to confirm selections

- Clench to open contextual menus

- Navigate via auto-scanning controls

Importantly, this functionality is integrated into watchOS without requiring additional hardware. The feature utilizes existing sensors, embedding accessibility within the device’s core system architecture.

Pinch & Double Pinch Gestures

The pinch and double pinch gestures allow users to move through and confirm selections without touching the screen. A single pinch typically moves the selection focus forward within a scanning interface, while a double pinch confirms or activates the highlighted option. Instead of requiring precise tapping on a small display

Through the medical model, this feature compensates for reduced fine motor precision. It recognizes that tapping a small display may be physically difficult and provides an alternative that restores interaction.

Through the social model, however, the issue is reframed. The barrier is not the user’s body, it is the interface’s assumption that touch precision is the only valid form of input. By allowing micro-gestures to function as commands, Apple expands what “normal” interaction means.

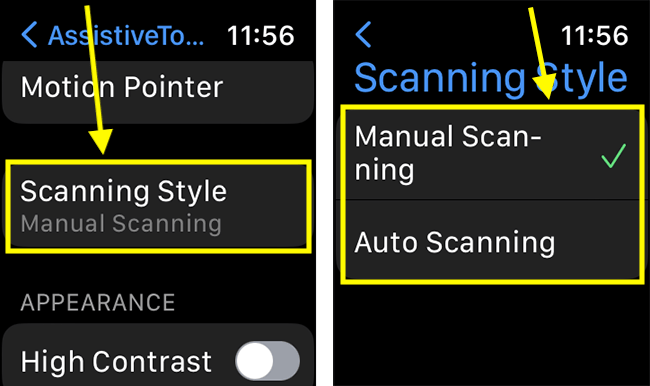

Auto-Scanning Interface

AssistiveTouch uses an automatic scanning system that highlights interface elements sequentially. For someone who has difficulty controlling their hand movements, tapping a tiny screen can be frustrating or impossible. Auto-scanning removes the need for accuracy and replaces it with a simpler action that is, waiting and selecting.

From a medical model perspective, scanning reduces the need for precise targeting, supporting users who may not have consistent motor control.

From a social model perspective, it acknowledges that the interface itself can create exclusion when it demands speed and accuracy. Auto-scanning redistributes cognitive and motor effort by adapting system behavior rather than expecting users to adapt to the system.

Conclusion

AssistiveTouch is not simply a feature that “helps” users with motor impairments. It represents a shift in how interaction itself can be designed. By recognizing wrist movements as intentional input, Apple moves beyond the assumption that touch precision defines usability. Through both the medical and social models, we see how the feature simultaneously compensates for physical limitations while also challenging the interface norms that create exclusion in the first place.

For me, AssistiveTouch reinforces an important lesson in product design: accessibility is not about reducing functionality, it is about expanding the possibility of usability. When we question default assumptions about how bodies interact with technology, we create systems that are not only more inclusive, but more innovative. Inclusive design does not restrict creativity; it deepens it.