Citymapper is used during navigation that involves high cognitive overload due to unfamiliar routes, or when a user is running late, or time sensitive travel. The goal of a typical user is simple- reach a destination efficiently, confidently, and on time. This critique evaluates whether Citymapper’s interface supports or complicates those goals through Don Norman’s design principles.

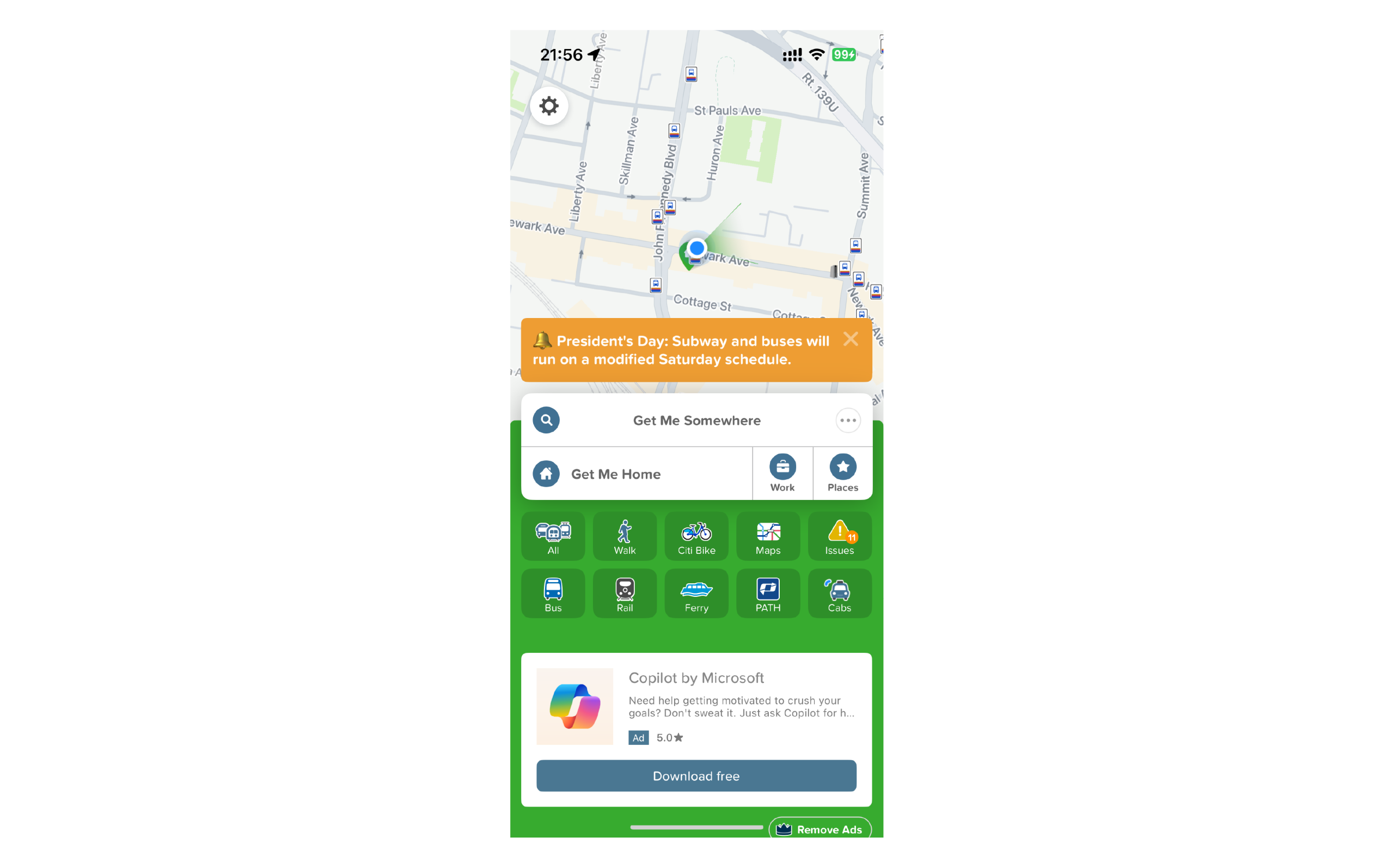

Home Screen

Citymapper’s homescreen uses affordances and signifiers well. The primary search bar with its labelled prompt “Get Me Somewhere” signals the action of what the system affords, clearly reducing ambiguity when the user begins navigating. Quick-access buttons for “Home”, “Work”, and “Places” enable users to act and function quickly with re-entering information- utilizing recognition rather than recall. The entire spatial layout aligns well with user intent, eventually minimizing the gulf of execution by making the primary action for the user which is starting a journey, immediately visible.

Additionally the interface utilizes cultural signifiers for the mode icons like bus, rail, ferry, walking, creating accurate expectations for users. It supports quick decision making, especially for regular users.

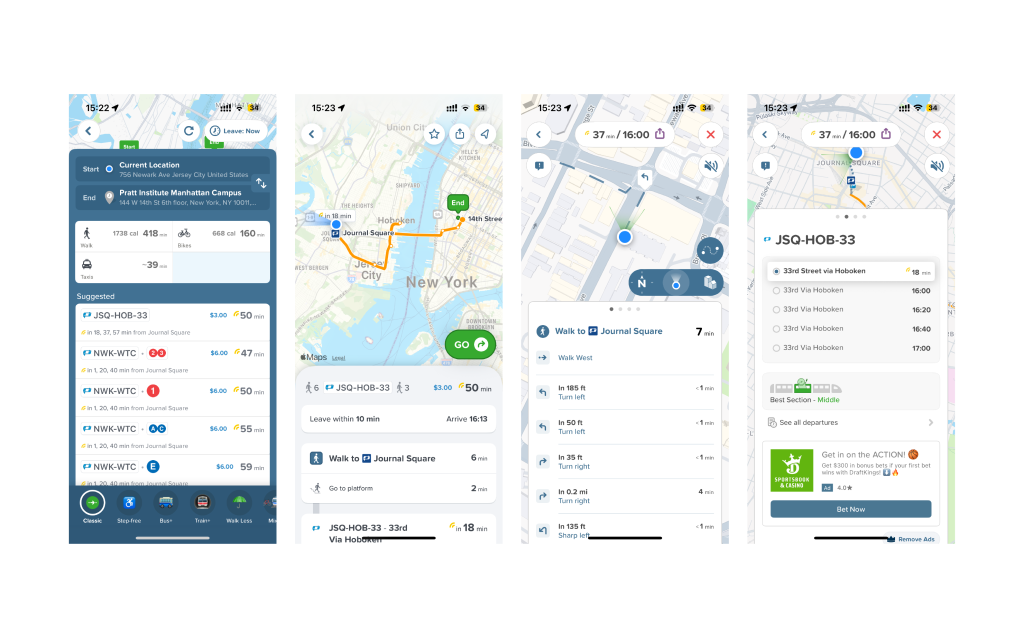

Real-Time Navigation

Citymapper excels at active navigation by providing continuous feedback and reflecting the visibility of system status. The interface continuously communicates the navigation status and updates itself along with the user’s movements through countdowns, live arrival times, stop counts and clear “Get off now” prompts. These cues reduce user anxiety by confirming timely updates and tracking the live journey.

Moreover, the feedback does not overwhelm the user but stays contextual. Relevant information appears at the appropriate time during the journey, reflecting how good design minimizes unnecessary memory load. This phase of the navigation perfectly bridges the gulf of execution.

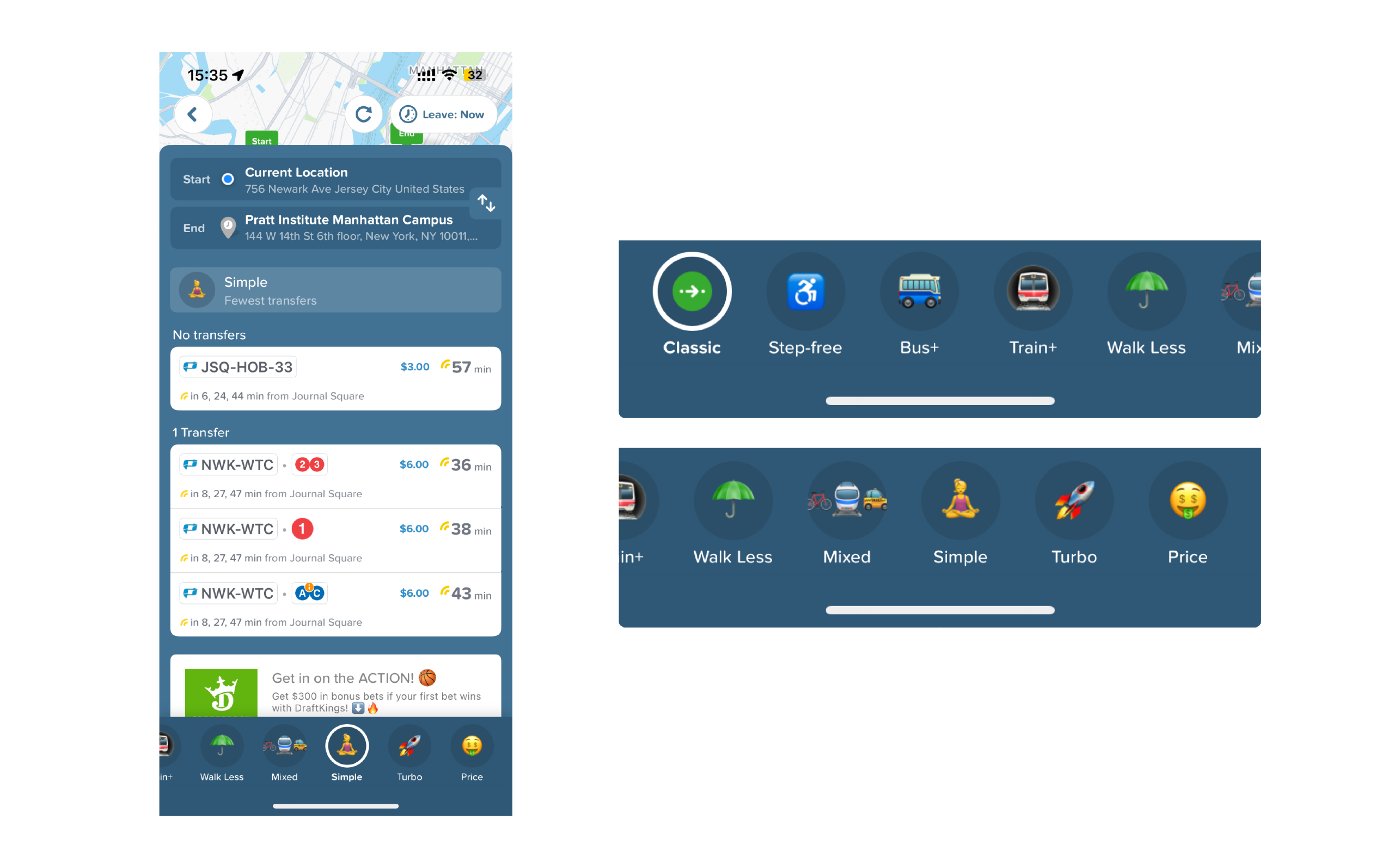

Mode Filters

Citymapper’s mode filters like Classic, Walk Less, Turbo, Price and so on act as well-designed constraints, that narrow down the routes based of user’s preference, enforcing user agency. The interface supports flexible route explorations by keeping these options as high-level preferences rather than rigid rules.

The “Step-Free” mode enables accessibility considerations. By keeping it as a primary interaction rather than relegating it to secondary settings, it supports inclusive design.

The visual consistency of these filters across the screens strengthens mapping, clearly depicting how these choices affect route generation for the users. This design choice reflects how good constraints are not restrictive but, enable users’ decision ability while reducing cognitive load.

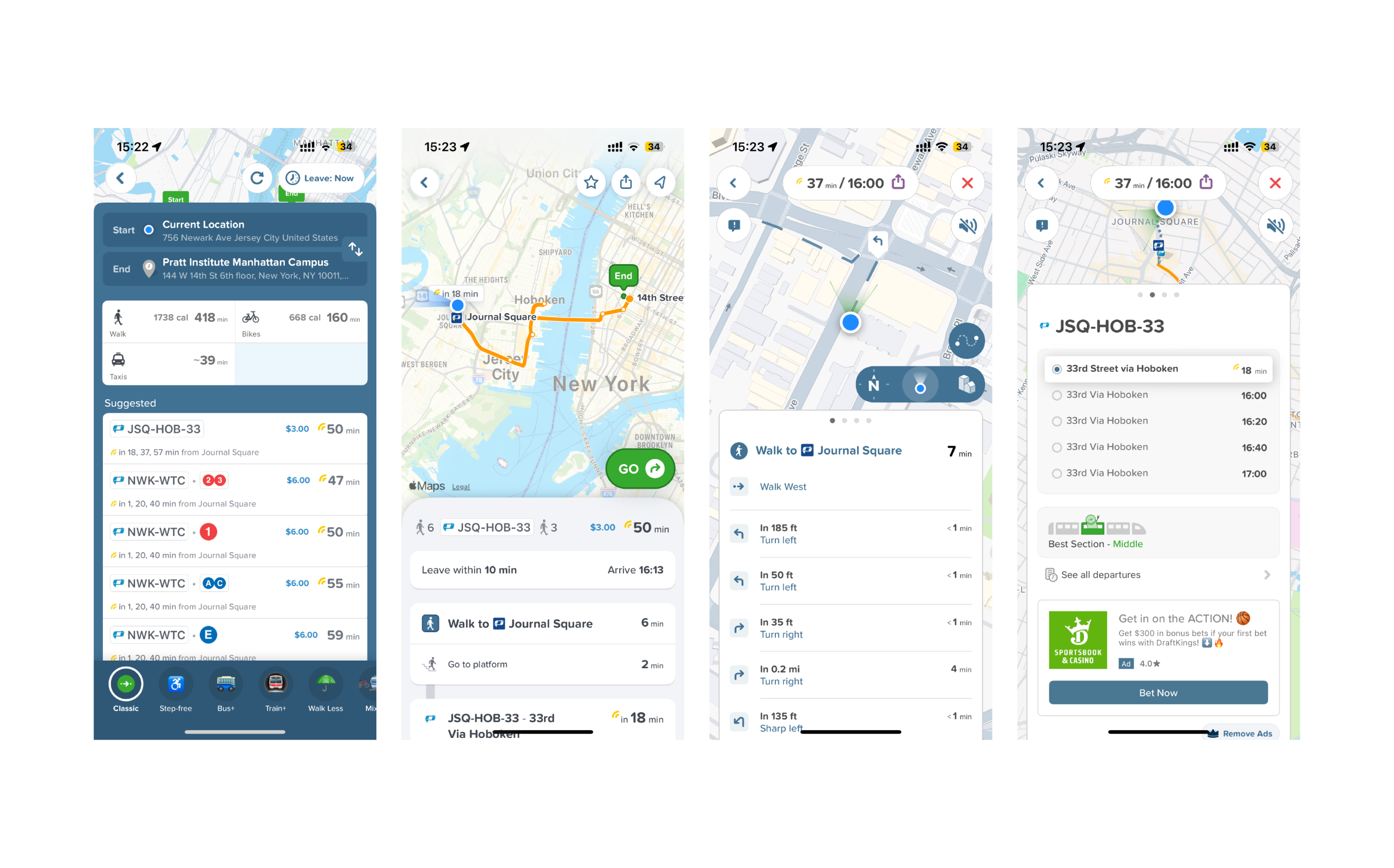

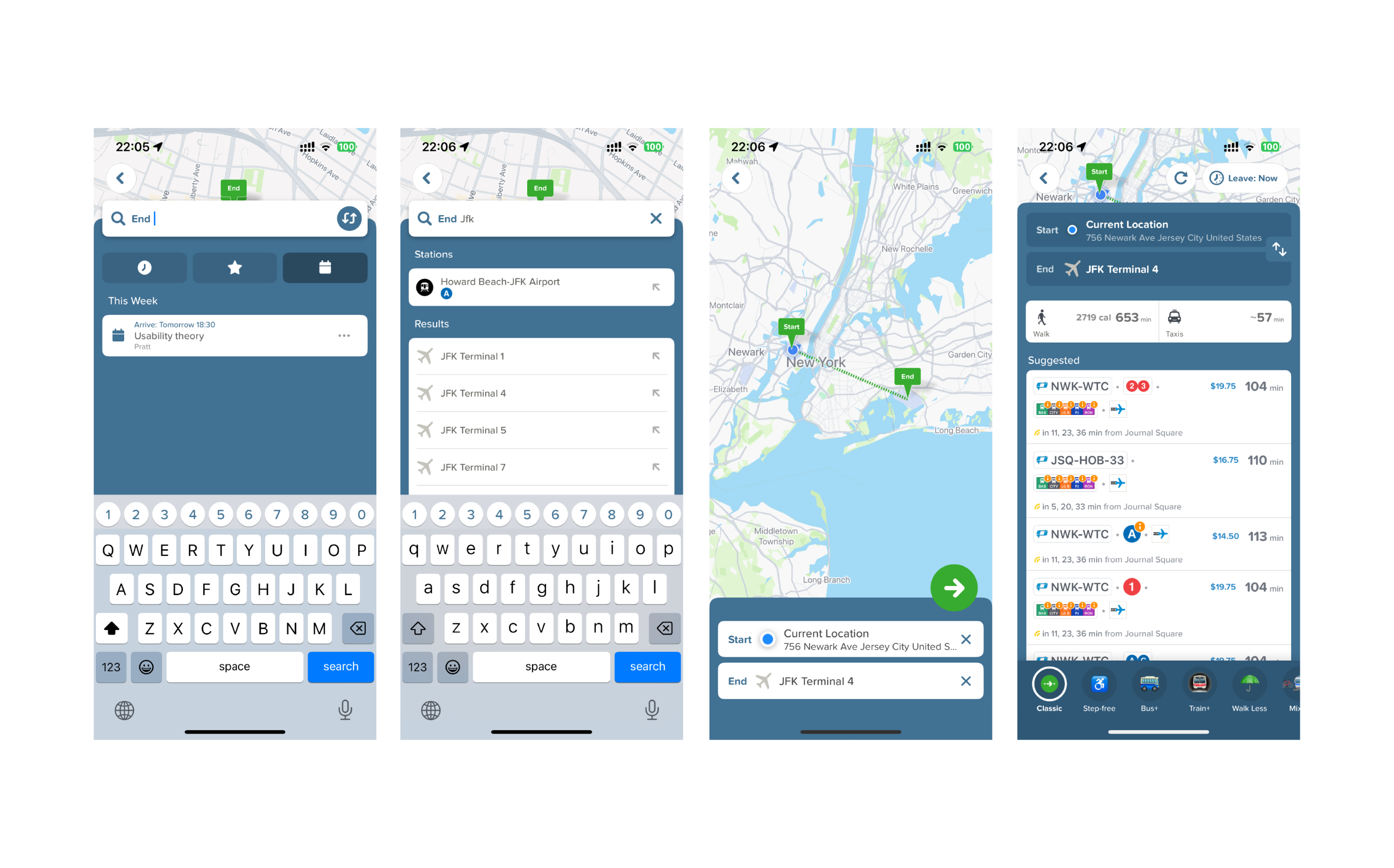

Scheduling a Trip

The schedule trip feature on Citymapper reveals a significant usability issue especially for time critical tasks. While it has a calendar feature integrated within it, the interface fails to identify time as its primary constraint when it comes to scheduling a trip.

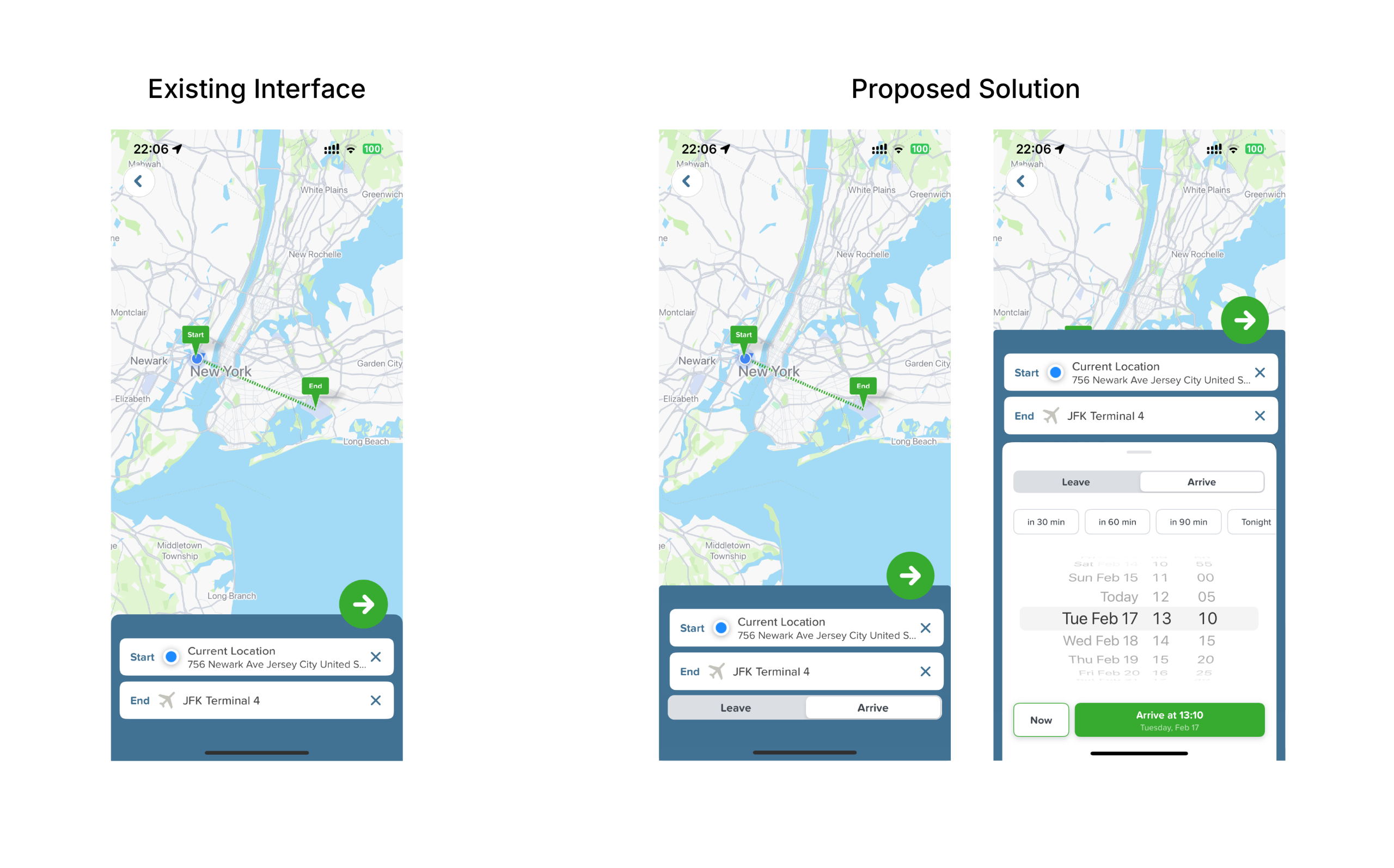

When scheduling a future trip manually (not tied to the calendar), the initial prompt is only restricted to “start” and “end” of the journey. The option to add time (leaving or arrival) appears much later in the process- embedded in a small “Leave: Now” white button at the top right corner which merges with the white map. The hidden control and poor contrast creates low visibility and the introduction of time as constraint at such a late-stage constraint increases user frustration and error risk. As a result, the gulf of execution widens since the users know what they want but, fail to communicate it with the system.

To address this issue, the user flow should introduce time selection alongside “start” and “destination”, rather than deferring it. Adding the “Leave at”/ “Arrive by” toggle in the initial planning stage would reduce the gulf of execution and better match with the user’s mental models.

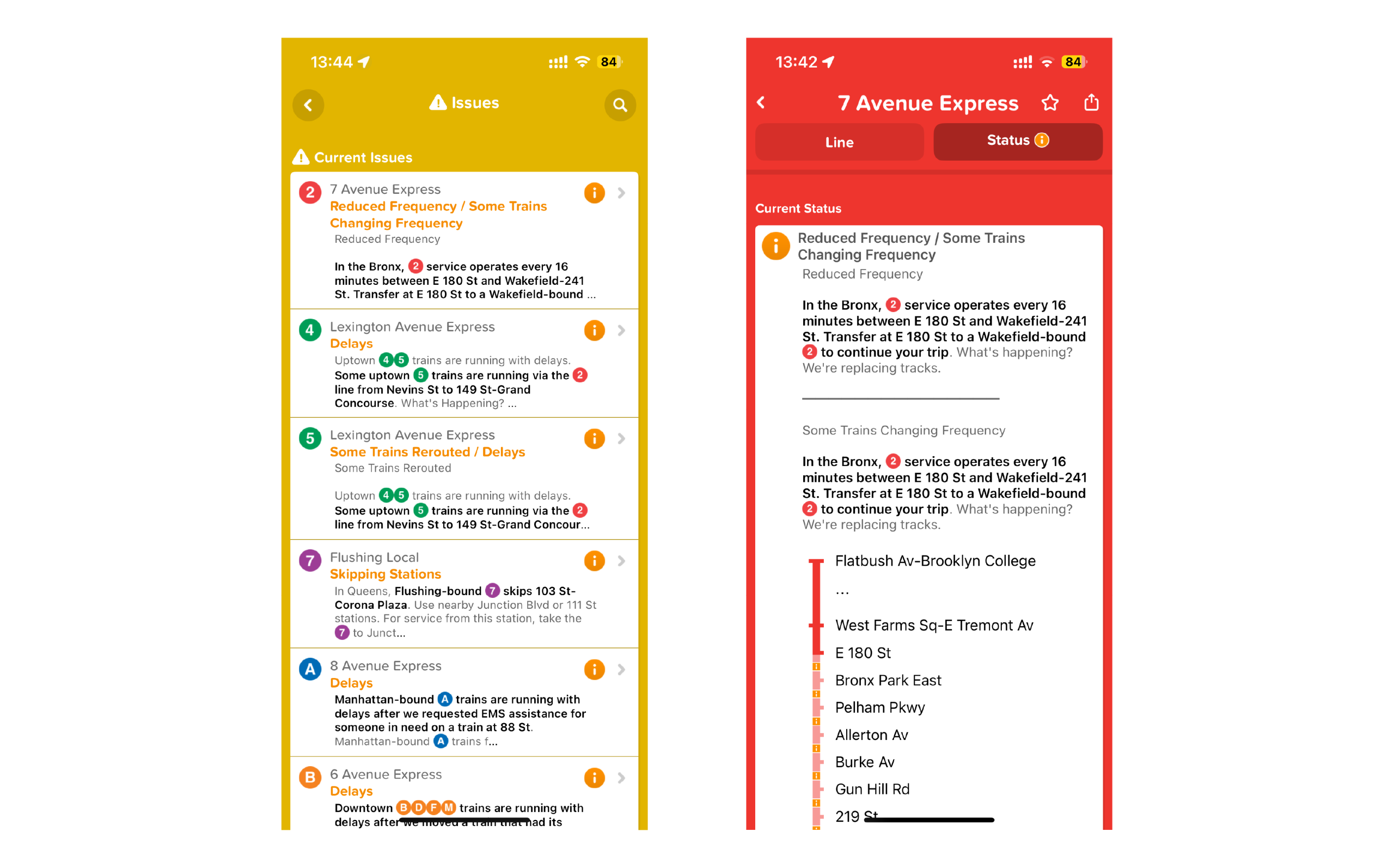

Issues and Disruption

The issues/disruption mentions delays, uncertain routes, service interruptions and advisories proactively and maintains visibility of system status. This transparency helps the user in avoiding error.

However the disruptions are system wide and generic rather than being route specific for the user, this weakens the mapping between the interface and users’ goal. Eventuall the users have to rely on knowledge in the head to infer whether disruptions affect their route, overall increasing the cognitive load.

The interface could potentially highlight those issues that directly affect the user’s journey and visually mark it on the map. A short message like “This delay affects your second transfer” would bridge the gulf of evaluation. By clarifying relevance of the issues and providing next steps to tackle the problem, the interface could strengthen users’ decision making under time pressures.

Conclusion

Citymapper demonstrates strong human-centered design supporting real-time navigation through clear signifiers, continuous feedback and effective constraints. However the challenges in scheduling a trip and disruption awareness clearly highlight how crucial introducing key constraints at the right time is, and how it can undermine critical user goals. Addressing this gap could potentially improve usability for time sensitive travel and immediate navigation, strengthening its overall usability and trustworthiness.