Abstract

Overview:

As the largest audio streaming service globally, the emotional experience of the Spotify app proliferates at a massive scale. This means that changes to its design and how it interacts with users’ emotions can have a significant impact, for better or for worse. For these millions of individuals, Spotify is one of the key portals available to them to engage with their (often all too limited) leisure time, and even turns what is otherwise “work” into a leisure experience. Users listen to music when they exercise, a podcast on their commute, and an audiobook while they make dinner. The content Spotify brings to users, such as music and podcasts, touches on a very emotional aspect of people’s daily experience: how they engage with art, news, education— things that feel meaningful to users.

Problem:

Spotify relies heavily on algorithmically generated content recommendations to keep users engaged. Users’ experience becomes increasingly negative the longer they sift through a constant stream of recommendations they perceive as irrelevant, with little ability to control what is presented to them, understand how recommendations are determined, and improve them by offering proactive feedback. This experience leads to emotions ranging from boredom to anger, resulting in negative emotional experiences for users

Research Questions:

Proposal:

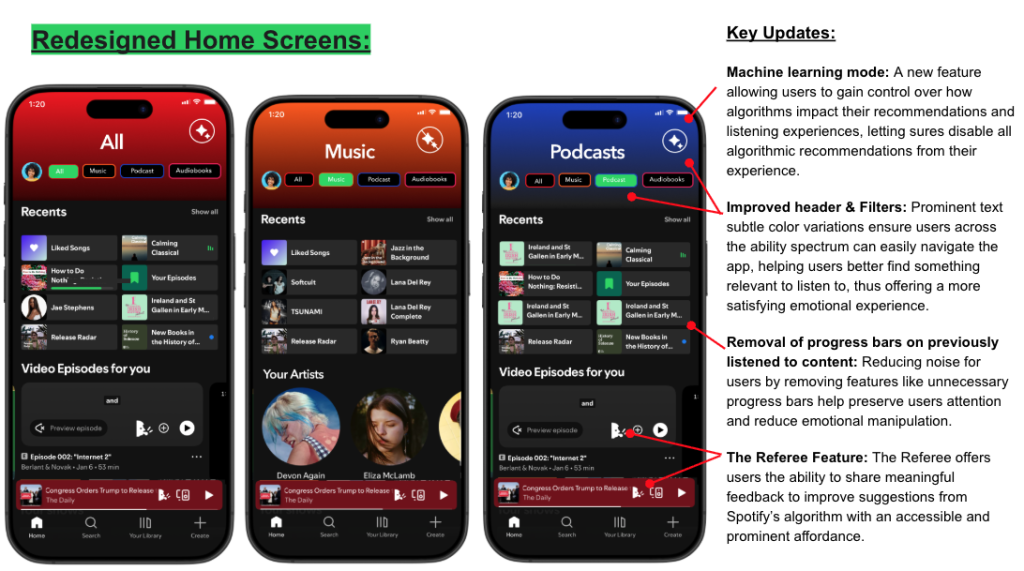

To solve this, I created redesign recommendations that offer new ways for users to manage their emotional experience, introducing functionality like a redesigned home page, “Machine Learning Mode”, and the “Referee” feature, focused on providing new paths to increase user agency and understanding. This redesign aims to reduce emotional manipulation and the mining of users’ attention, offering a more ethical and satisfying user experience. Updates allow users to take more control of their experience by removing suggested content, sharing relevant feedback, and better controlling and understanding the application. These updates help enhance the positive and meaningful experience of engaging with music or podcasts while reducing the negative emotions like anger or fear associated with the oppressiveness of algorithmic suggestions in the attention economy.

Introduction

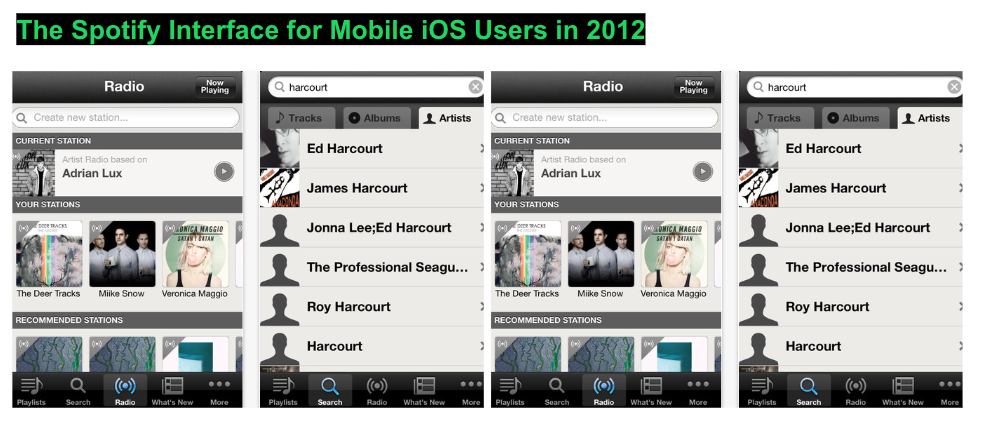

I became a Spotify user in 2012, in the burgeoning world of social media and streaming. At the time, Spotify felt completely revolutionary: for around $10 a month, one had access to essentially all publicly available music. Not-so-coincidentally, it was around this time that smartphones began to proliferate, with nearly half of Americans owning a smartphone in 2012, up from 33% the year before (Smith, 2012). Liberated from the chains of purchasing single songs or albums on iTunes or encountering irritating (albeit comical) local radio advertisements, we were free to discover music with dignity. Spotify’s enhanced discoverability and personalization offerings, such as the “radio” feature, the “what’s new” tab, and its integration with social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter, made it an optimal environment for exploring and listening to music in the digital age. Listening to music felt more interactive, engaging, and exciting than ever, and with a smartphone, more accessible.

Source: the Internet Archive

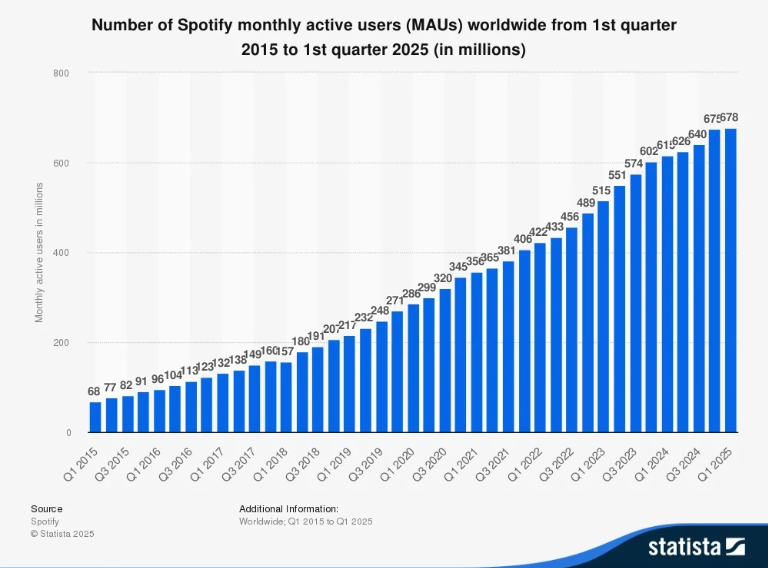

Thus began our collective journey toward a society dominated by the production and consumption of content, which itself became increasingly controlled by “the algorithm”. Spotify, along with companies like Netflix, Instagram, and Amazon, were pioneers in the emerging “platform economy”, defined by the economic activities on online marketplaces that connect suppliers with consumers, characterized by its reliance on technologies such as algorithms and cloud computing to drive efficiencies and dictate user experiences (Sheposh, 2025). Spotify, connecting users with what I’ll hesitantly refer to as “content”, altered the traditional means of distribution, such as radio stations and brick-and-mortar stores, to act as the intermediary offering direct access between the consumer and the producer. This model proved immensely successful in the market, with Spotify leading the music streaming industry with 713 million monthly active users as of November 2025, driving revenue up 12% year over year to 4.3 billion Euros for the third quarter of 2025 (Spotify Technology S.A., 2025).

The growth of Spotify’s monthly active users globally, from Q1 2015 – Q1 2025. Source.

Despite Spotify’s success over the past decade and a half, as a user, I often (and increasingly) find myself frustrated, angry, and resigned in my experience using the app. Disenchantment and malaise have set in, replacing my once fervent enthusiasm for what it offered me. But what changed?

As the largest audio streaming service globally, the emotional experience of the Spotify app proliferates at a massive scale. This means that changes to its design and how it interacts with users’ emotions can have a significant impact, for better or for worse. For these millions of individuals, Spotify is one of the key portals available to them to engage with their (often all too limited) leisure time, and even turns what is otherwise “work” into a leisure experience. Users listen to music when they exercise, a podcast on their commute, and an audiobook while they make dinner. The content Spotify brings to users, such as music and podcasts, touches on a very emotional aspect of people’s daily experience: how they engage with art, news, education— things that feel meaningful to users.

Critical Analysis

As a Spotify user, I appreciate having a centralized place for all my audio-based consumption, namely music and podcasts. While the consolidation is desirable, it also creates a somewhat clunky user experience both technically and emotionally, where finding the right thing to listen to can be cumbersome and disatisfying. This user journey causes negative emotions, such as annoyance, sadness, boredom, and disapproval, to arise and color one’s experience. In this section, I am to evaluate the information architecture, app design, and users’ emotional journeys in Spotify’s iOS app. Through a critical analysis, I aim to propose solutions that create a more emotionally satisfying user experience.

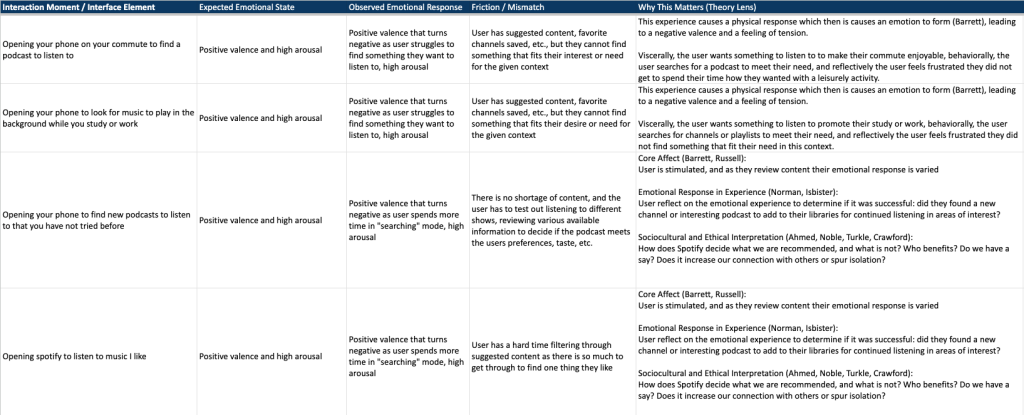

To understand the emotional experience of using Spotify to find something to listen to, I created an emotional friction map based on my own experiences.

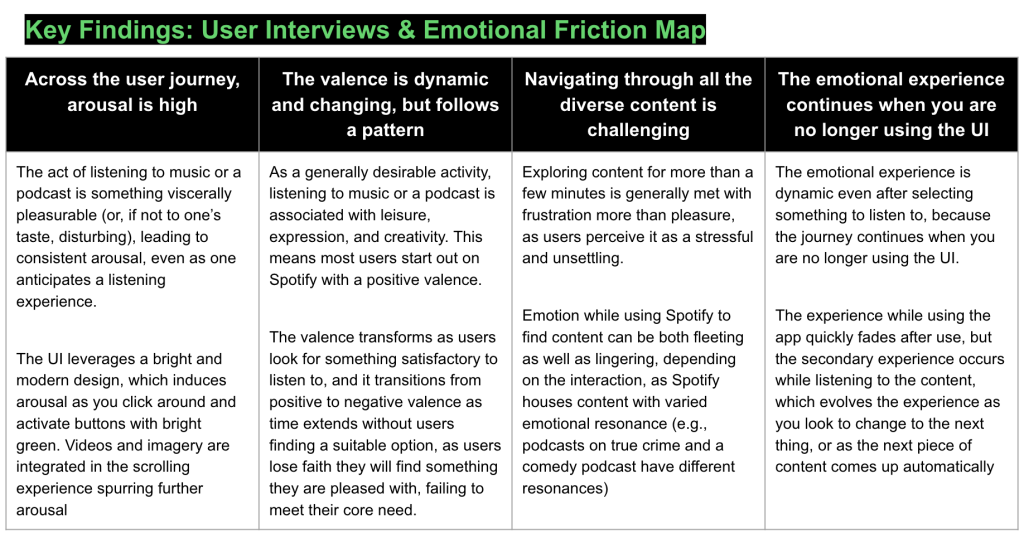

Next, I interviewed a handful of Spotify subscribers (n=4) to evaluate their emotional experiences using the iOS app’s interface, considering the application’s affordances, feedback loops, friction, and mismatches. In this analysis, a few key themes emerged:

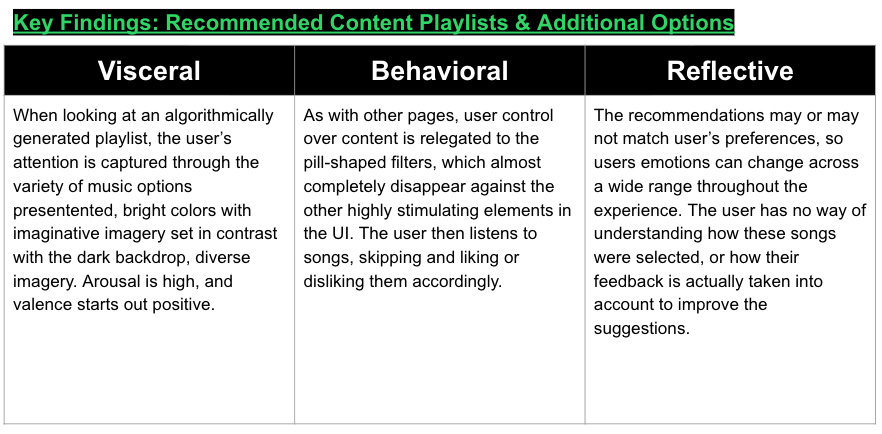

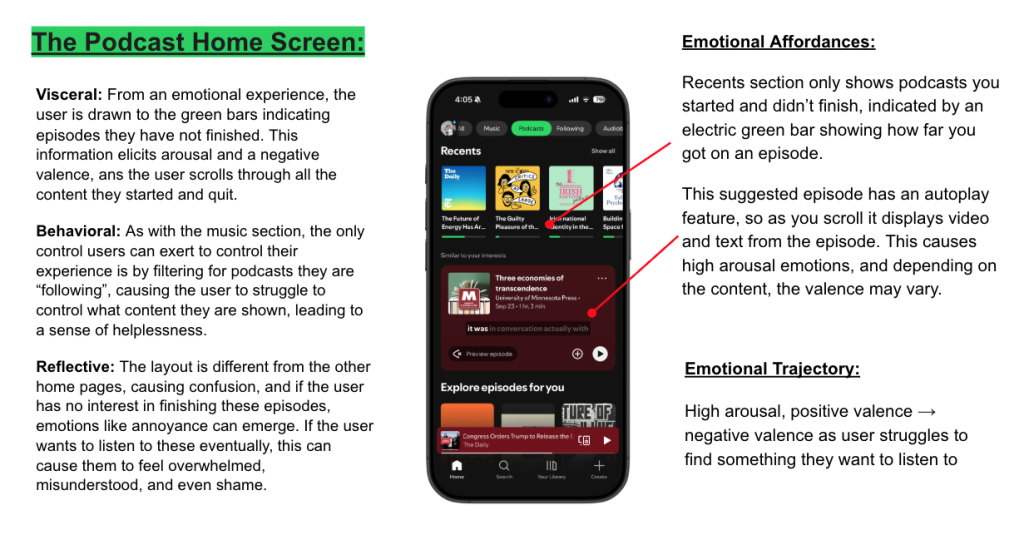

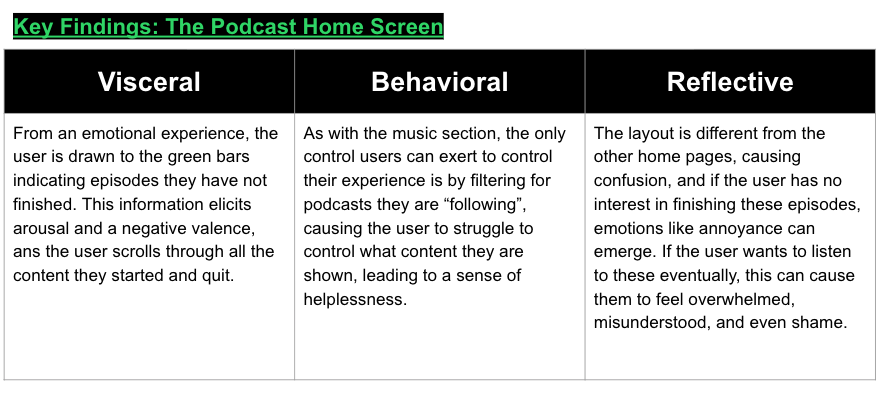

To better understand how these issues manifest in an emotional design problem, I analyzed Spotify’s iOS interface using Don Norman’s Three Levels of Emotional Processing—Viceral, Behavioral, and Emotional—outlined in his book, naturally titled Emotional Design. This framework helped establish the levels at which emotions are felt while using Spotify to better organize the solution around solving the user’s core needs at each level.

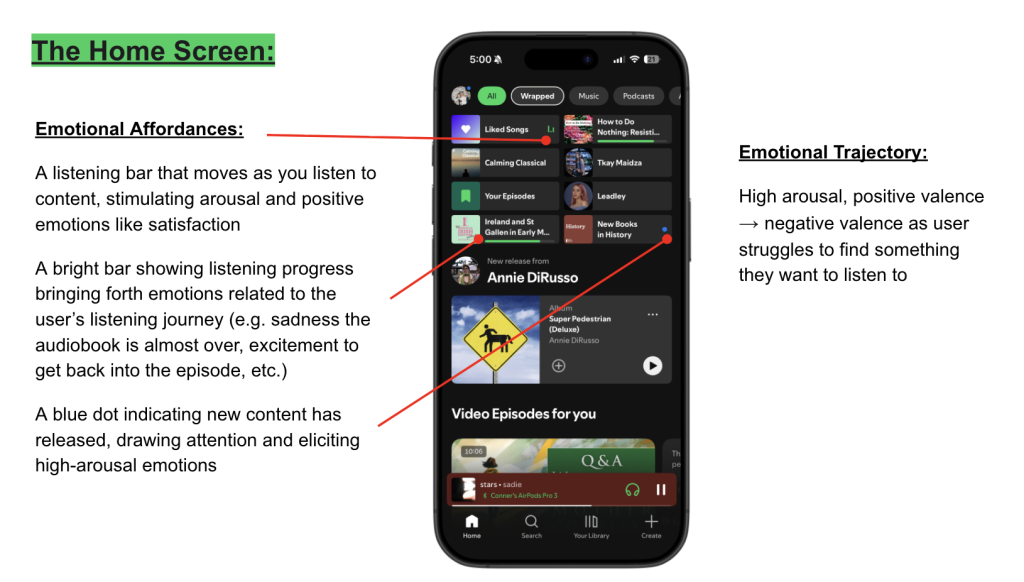

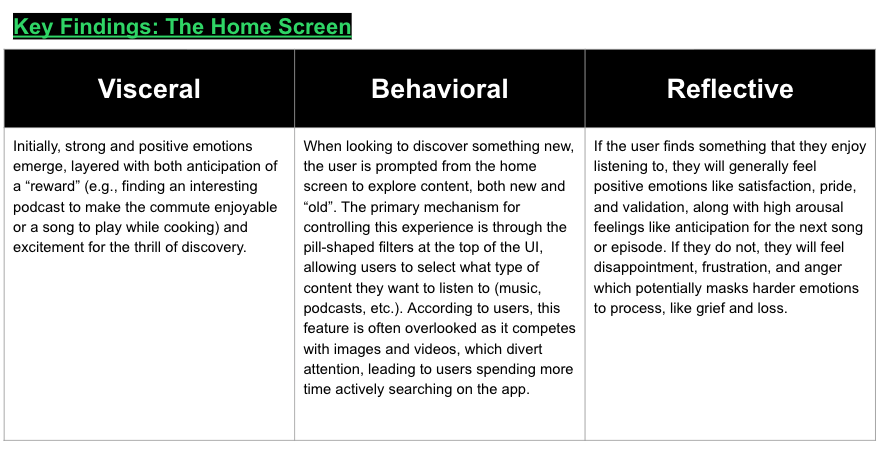

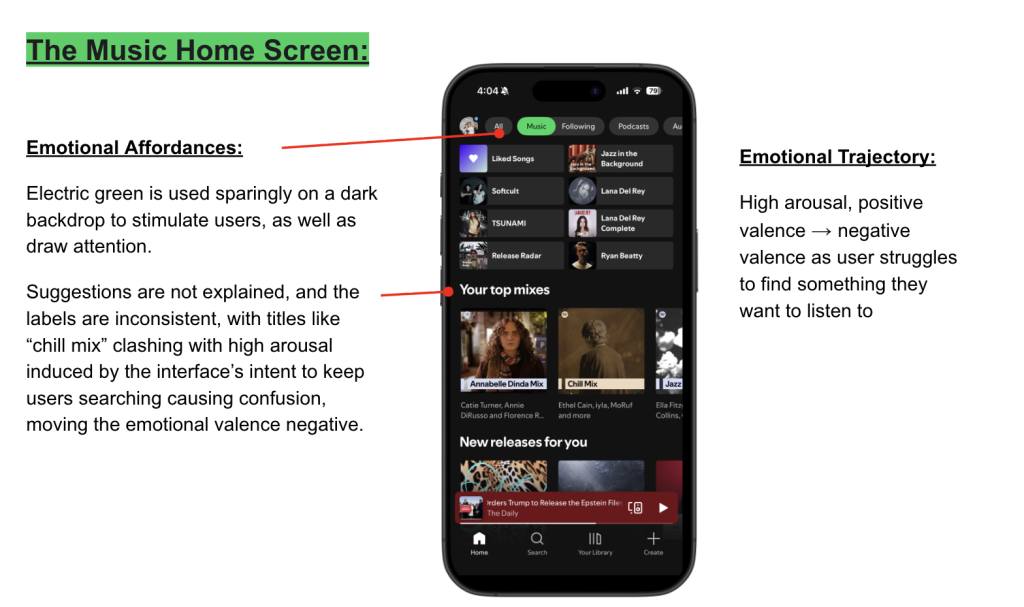

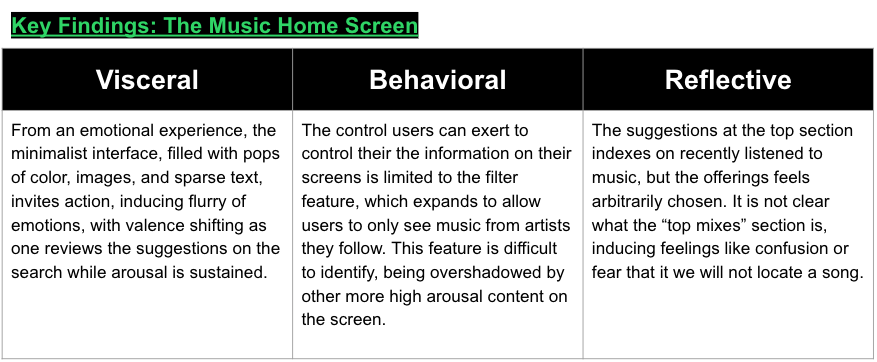

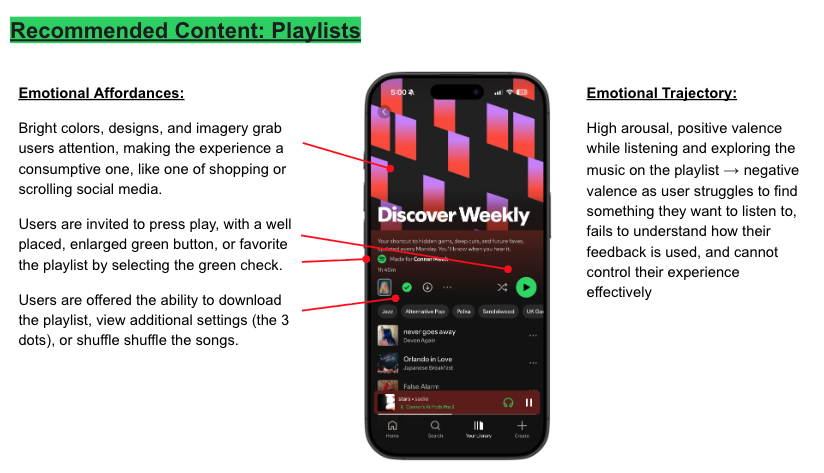

From my research, it appears most users begin their journey on the home screen, where they are presented with a myriad of options to explore. If a user knows what they want to listen to, finding that song or podcast is generally pretty seamless and effective, due to well-functioning and accessible search functionality. The emotional experience becomes higher stakes when a user is unsure exactly what they want to listen to, requiring them to navigate through the app to locate something that satisfies their preferences and current context.

With seemingly endless stores of music, podcasts, and now audiobooks, deciding what to listen to on Spotify can be difficult. To solve this, Spotify famously provides recommendations, ostentatiously designed to help you search for your next listen. While these recommendations come in many forms, from tailored playlists to radio and DJ features, nearly all of them have one unifying theme: they are algorithmically determined.

In the current Spotify experience, one particular usability feature kept surfacing as the source of frustration and anger: the filtering system. Spotify offers small, pill-shaped filters at the top of a page or playlist to control, to a limited degree, what type of content you are shown. It is generally the only lever at the user’s disposal to take control of what is shown on their screen, and yet, it is barely perceptible. 3 out of 4 users I spoke with stated they often overlook this affordance, and have blamed the filter design for unsatisfying user experiences in the past.

Many recommendations come in the form of playlists. According to Spotify, even their playlists, which are created by their Editorial team, leverage Spotify’s algorithmic technology to control the user’s listening experience (Spotify, 2023). On a high level, Spotify’s algorithm leverages machine learning to analyze user behavior and predict what they will want to listen to. They then extrapolate an “understanding” of a user’s preferences, and the algorithm determines what song to play next in the playlist (Spotify, 2023). This approach to directing the user experience is billed as engaging, suggesting that the algorithm, considering every save, skip, and listen, is an opportunity to train the algorithm to uniquely adapt to one’s needs, taste, and desires. As predicted by Rosland Picard in her book Affective Computing, this approach to technology indicates a belief that “affective computers should not only provide better performance in assisting humans, but also might enhance computers’ abilities to make decisions.”(Picard, 1997). While this logic may be coherent, it attempts to adhere to something as human as emotions and feelings with the values of business and productivity, overlooking any meaningful consideration of the emotional experience of users.

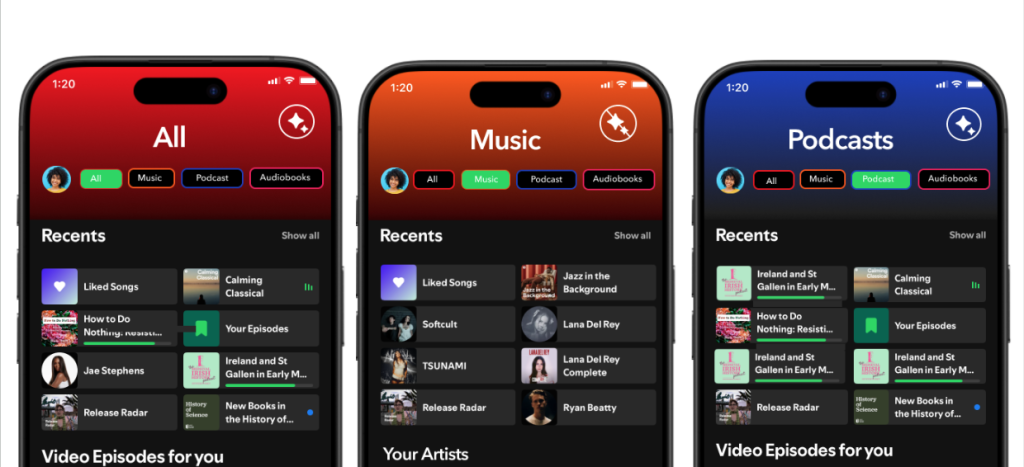

The interface is also hard to pin down, changing how recommendations are presented depending on what you are looking for. For podcasts, it shows “Recents” at the top, but for music or the “all” page, it shows an assortment of options in a 4×2 table. This inconsistency creates a disorienting experience, leading to feelings of anger, fear, and dread.

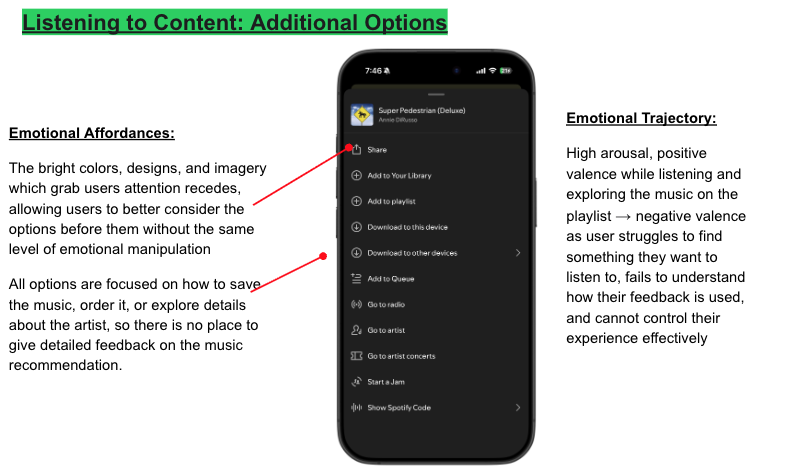

After viewing or listening to a suggestion, Spotify offers limited information for understanding why you were shown a particular recommendation. Outside of adding a song to your “favorites” list or selecting “x,” which lets you block that song or artist for 30 days, users cannot share more specific and useful feedback to improve their suggestions.

Considering these insights, I developed a series of potential solutions to the emotional challenges experienced by users on Spotify, aimed at providing greater user agency, transparency, and relevance, ultimately leading to positive and enriching emotional experiences for users.

Recommendations

In my redesigns, updating the home screen experience is critical in improving the emotional journey of users. As the launch pad for their user journey on Spotify, my suggested redesign focused on addressing the sources of negative emotional experiences by adding new affordances, updating the information architecture, and improving usability.

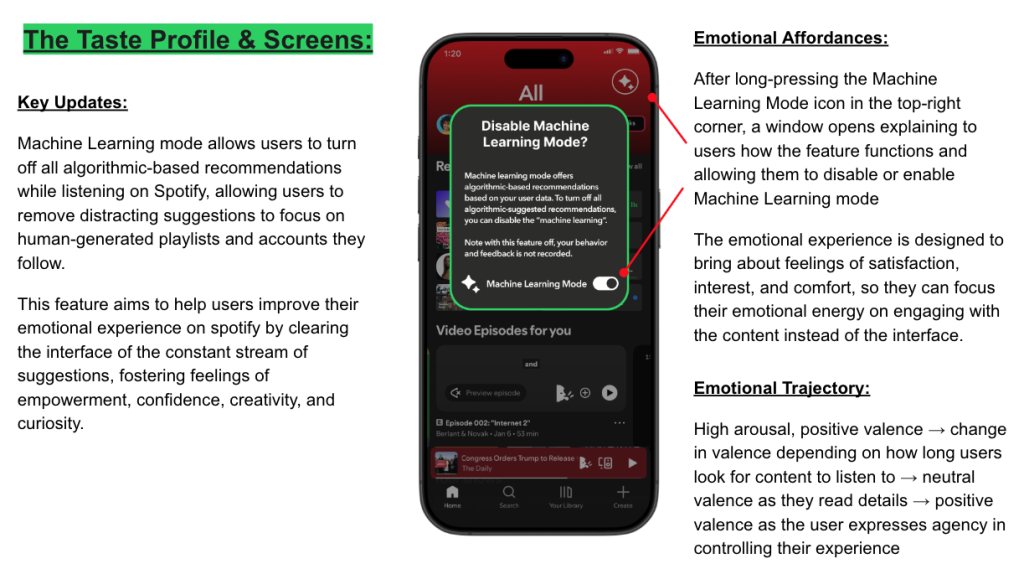

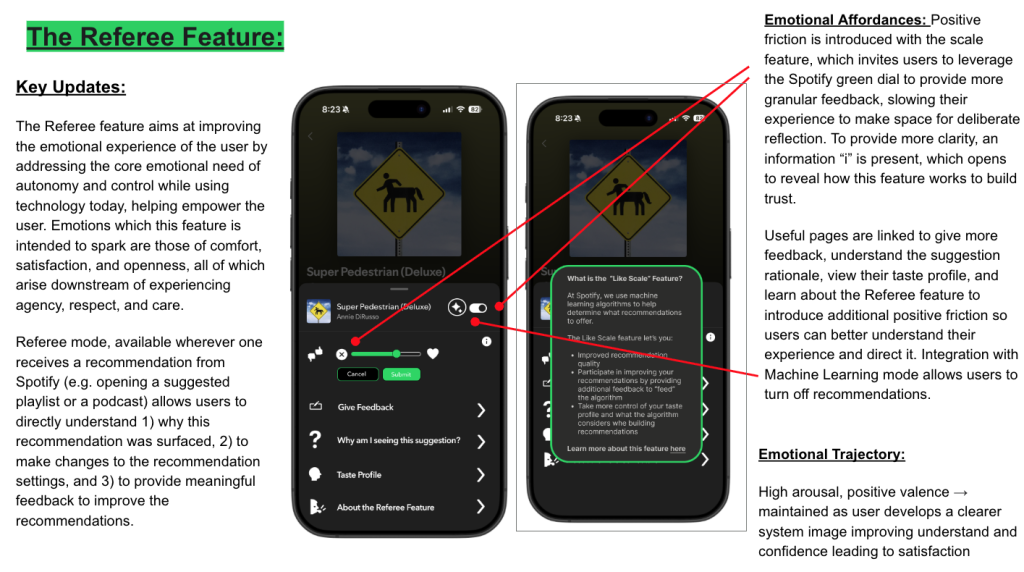

The newly designed “Referee feature” and the “Machine Learning Mode” help users understand and improve their recommendations, or remove them entirely, as shown in the “Music” homescreen, which has no algorithmically suggested content. This environment sets the stage for more user-directed experiences, favoring active participation over passive scrolling. Introducing friction across the UI supports a more deliberate experience for users while engaging with music or a podcast.

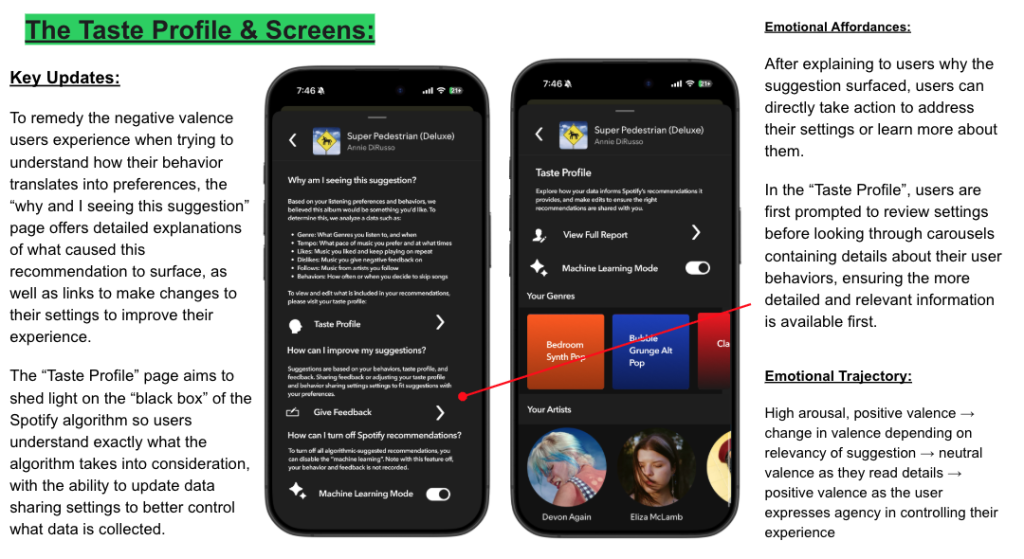

An important feature of this redesign is to offer users more information, not less. Spotify’s interface traditionally provides little in terms of descriptors, making it hard for users to understand why they are seeing certain things, leading to negative emotions like rage or panic. The “Machine Learning Mode” descriptors seek not to solely direct a user, but to inform them.

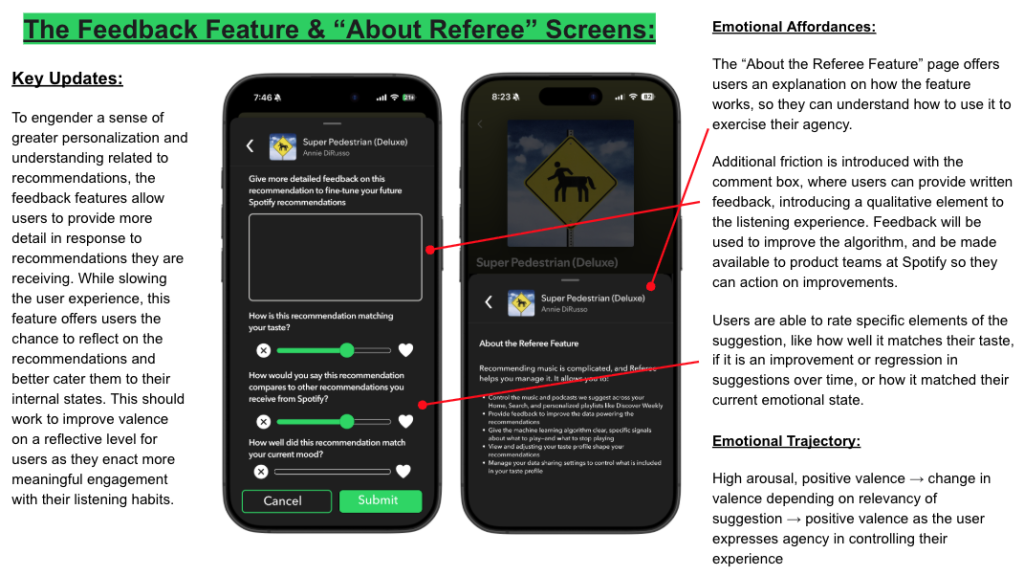

As we have discussed, the current interface offers little to no way for users to actively participate in providing feedback. The Referee feature seeks to solve this by integrating wherever a user is confronted with a recommendation, equipping users with what they need to fight bad recommendations and distressing data use and collection practices.

Today, users are assigned a “taste profile,” a key element in Spotify’s algorithmic recommendations system, which is not accessible to users today. To increase transparency and control, my redesigns bring this directly to the user with a “Taste Profile” page, easily accessible through the “Referee” feature or their settings. With this page, users can control what the system records about them, how their data is used, and what recommendations look like.

Discussion

While the details of our collective descent into an algorithmically-driven feedback loop are new and specific to the stage of the digital age that emerged in the 2010s, one may consider the process a feature rather than a bug. Capitalism, intent on locating and exploiting any slice of reality for the purposes of generating capital, has experienced continued deregulation and expansion since the Reagan administration of the 1980s. The advent of new digital technologies opened the door to new and increasingly insidious efforts to commodify our attention.

Jenny Odell, in her book How to do nothing: resisting the attention economy, writes extensively on the nature of this exploitation, what it would mean to separate oneself from the attention economy, and, most importantly, what would be gained. While I more or less agreed with her proposition that resisting the attention economy, focusing on a return to an authentic participation in the natural world, is probably the best thing one can do to cope with the malaise of our time, I also really like having an on-demand music streaming service.

In Alone Together, Sherri Turkle, a professor at MIT, explores the means by and degree to which technology’s assault on our attention has alienated us from the world and each other. With endless possibilities and options available to us and ostensibly attainable, our base instincts to scavenge, search, and hunt for the next or best thing are naturally exploited to drive engagement on platforms. According to Turkle, the tethered self of today is constantly in a state of distraction, spending less time considering our own opinions, thoughts, feelings, and goals. To address the challenges presented by the mining of our attention, increasing positive friction in the interface design is a step in the right direction, but it remains to be seen how well these proposed design solutions may actually reduce distraction or “disconnectedness” in the face of the attention economy’s magnetic forces.

The conundrum I find myself in is not lost on me, where, on one hand, I am criticizing capitalism and the means by which its practices infiltrate and degrade our daily emotional experiences, while offering suggestions for improving a consumer product, tacitly approving of the use of algorithmic “control” on users. I am reminded of the late Mark Fisher’s statement in Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? “It’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.” (Fisher, 2009). I believe my proposed redesigns offer an acceptable compromise, offering users greater choice and the option to remove algorithmic controls from their experience entirely, but I worry that this approach, while practical in theory, assumes that we are able to control more than we are.

In his 2021 documentary Can’t get you out of my head: An emotional history of the world, Adam Curtis explores (among many things) the ideas of B.F. Skinner, the psychologist famed for his theories on human behavior, proclaimed in his 1971 book Beyond Freedom and Dignity that the concepts of free will as we traditionally understand them are outdated and problematic. Skinner believed that behavior is determined not by an individual “self” but by the environment, and to construct a better future, we must focus on scientifically verifiable and behavioral phenomena, renouncing concepts such as freedom or dignity as no longer useful. Curtis posits an alternative to this thinking, considering findings from eBay indicating paid advertisements may not actually control our behavior, signaling we may not be as easily manipulated as we believe. I find this idea both compelling and beautifully optimistic, as Curtis summarizes with a quote from David Graeber: “The ultimate, hidden truth of the world is that it is something that we make, and could just as easily make differently.”

Conclusion

To describe the process in which capitalism has manifested in the platform economy, Cory Doctorow, a writer and journalist, coined the term “enshitification”. Doctorow describes enshitification in stages: “First, platforms are good to users; then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers; finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves. Then, they die.” (Doctorow, 2023). There are numerous examples of this, from social media companies like tik tok or instagram increasingly focusing on leveraging algorithms to keep users engaged while scaling monetization efforts through advertising and ecommerce to delivery companies like Doordash, which leveraged a discounting strategy to get customers hooked on the service, thus creating an environment where couriers and restaurants were reliant on food deliver companies before raising prices. Doctorow believes this process is inevitable, on account of both the control they exert in allocating value among stakeholders and a platform’s nature as a two-sided marketplace in which it holds each side hostage to one another (Doctorow, 2023). In the case of Spotify, this is described in the book Chokehold Capitalism, which outlines how Spotify colludes with music labels to extract value from creators to the benefit of shareholders (Giblin & Doctorow, 2022).

In an effort to “de-shittify” an app I am an avid user of, I created redesigns of the Spotify iOS interface aimed at giving back control to users and improving their emotional experience in the process. As the largest music streaming platform globally, I hope that in the future steps are taken to offer a richer emotional experience. In my view, the future of consumer-facing technology, contrary to conventional wisdom of the current climate, is about increasing agency and reducing our reliance on machine learning and “artificial intelligence”, which offers a mundane and controlled user experience. The intent behind these proposed redesigns is to provide users with more choice, reducing constant engagement in favor of a deeper, more enriching emotional experience. The ultimate goal of Spotify’s interface design from an emotional design perspective should be to support the emotional experience specific to one’s context rather than derailing or detracting from it.

References

Barrett, L. F. (2017). How emotions are made: The secret life of the brain. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Barthle, C., & Spotify. (2023, April 27). Humans + Machines: A look behind the playlists powered by Spotify’s algotorial technology. Engineering At Spotify. Retrieved December 8, 2025, from https://engineering.atspotify.com/2023/04/humans-machines-a-look-behind-spotifys-algotorial-playlists

Curtis, A. (Writer/Director). (2021). Can’t get you out of my head: An emotional history of the world [Television series]. BBC

Crawford, K. (2021). Atlas of AI: Power, politics, and the planetary costs of artificial intelligence. Yale University Press.

Doctorow, C. (2023, January 21). Pluralistic: Tiktok’s enshittification (21 Jan 2023). Pluralistic: Daily links from Cory Doctorow. https://pluralistic.net/2023/01/21/potemkin-ai/#hey-guys

Fisher, M. (2009). Capitalist realism: Is there no alternative? Zero Books.

Fisman, R. (2013, March 11). Did eBay just prove that paid search ads don’t work? Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2013/03/did-ebay-just-prove-that-paid

Giblin, R., & Doctorow, C. (2022). Chokepoint capitalism: How big tech and big content captured creative labor markets and how we’ll win them back. Beacon Press.

Holmes, K. (2018). Mismatch: How inclusion shapes design. MIT Press.

Norman, D. A. (2004). Emotional design: Why we love (or hate) everyday things. Basic Books.

Odell, J. (2019). How to do nothing: Resisting the attention economy. Melville House.

Picard, R. W. (1997). Affective computing. MIT Press.

Sheposh, R. (2025). Platform economy. Research Starters. EBSCO. Retrieved December 8, 2025, from https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/technology/platform-economy

Skinner, B. F. (1971). Beyond freedom and dignity. Knopf.

Smith, A. (2012, March 1). Nearly half of American adults are smartphone owners. Pew Research Center. Retrieved December 7, 2025, from https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2012/03/01/nearly-half-of-american-adults-are-smartphone-owners/

Spotify Ltd. (2012). Spotify (0.5.6) [Mobile app]. App Store. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20120915014127/http://itunes.apple.com/us/app/spotify/id324684580?mt=8

Spotify Technology S.A. (2023, October 18). How Spotify uses design to make personalization features delightful — Spotify. Spotify Newsroom. Retrieved December 8, 2025, from https://newsroom.spotify.com/2023-10-18/how-spotify-uses-design-to-make-personalization-features-delightful/

Turkle, S. (2011). Alone together: Why we expect more from technology and less from each other. Basic Books.