Introduction

I got my first pair of Apple AirPods about a week ago and while exploring its features, I was surprised to learn that they can also function as hearing aids for people with hearing disabilities, something that was also discussed on the first day of our digital accessibility class.

This discovery was particularly intriguing because it challenged my initial perception of AirPods as a purely consumer-focused product rather than an assistive technology, revealing a gap in my own understanding shaped by a lack of prior education around accessible and inclusive design. Before learning more about assistive technologies, I had not fully considered how everyday products can meaningfully support people with disabilities or how accessibility is often intentionally embedded into mainstream design. Viewing AirPods through the social model of disability reframed them as a product that reduces disabling barriers by integrating assistive features into technologies people already use, rather than separated into specialized tools.

Apple – Mastering Accessible Design

Apple’s approach to accessibility extends across many of its products, embedding inclusive features directly into mainstream devices rather than treating them as add-ons. Tools such as VoiceOver, Live Captions, AssistiveTouch, and Sound Recognition on iPhones are built into iOS and macOS and are available to all users by default. These features support people with visual, hearing, motor, and cognitive disabilities, while also benefiting users in temporary or situational contexts, such as hands-free use or noisy environments. By integrating accessibility into core system settings, Apple normalizes the use of assistive technologies and reduces the stigma often associated with specialized devices.

Evaluation of Apple AirPods as an AT

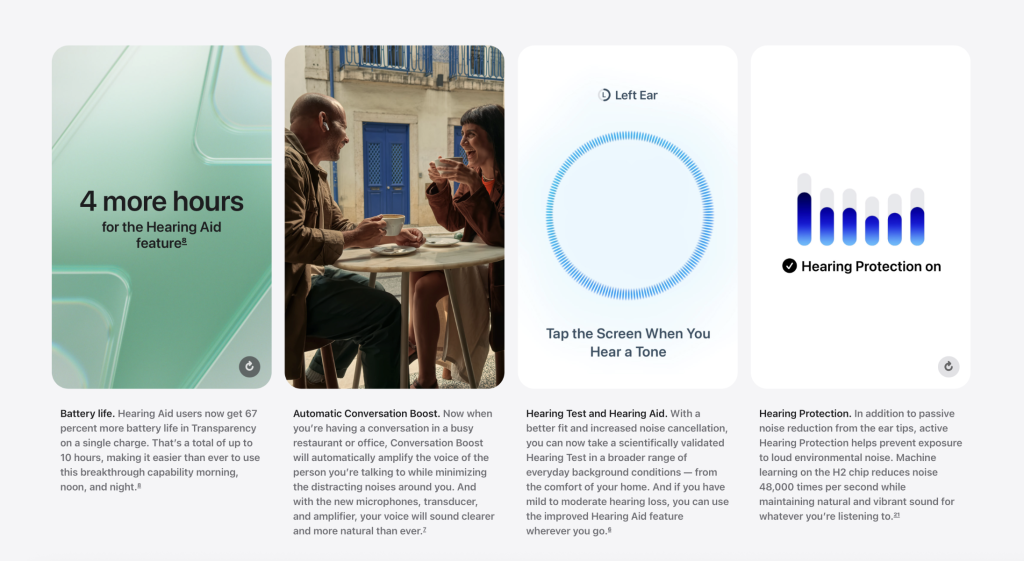

Apple AirPods are primarily marketed as consumer wireless earbuds; however, recent iterations, particularly the AirPods Pro (2nd gen), also function as assistive tools for users with hearing disabilities. With features such as Live Listen, Conversation Boost, Customized Sound and support for Over-the-Counter (OTC) hearing aid functionality, AirPods present a compelling example of inclusive design embedded within mainstream technology.

Looking at the Apple AirPods through the lens of disability models, it can be understood as a compensatory tool designed to mitigate individual hearing impairment. The AirPods Pro 2 are capable of functioning as OTC hearing aids, and studies have shown that they can perform similarly to basic hearing aids in quiet environments. Features such as sound amplification and noise control with adaptive technology allow users with mild to moderate hearing loss to better perceive speech, particularly in controlled settings. In this sense, AirPods aim to address hearing loss by enhancing auditory input, aligning with the medical model’s focus on treating or correcting impairment at the individual level. However, this approach remains limited, as it does not fully account for complex or severe hearing needs that require clinical support but rather as sound amplifiers.

Closely related is the functional model, which frames disability in terms of practical problem-solving. From this perspective, AirPods offer a convenient, everyday solution that enables users to hear more clearly without requiring specialized or clinical equipment. With enhanced noise cancellation, users can take a scientifically validated Hearing Test from the comfort of their home, and those with mild to moderate hearing loss can use the built-in Hearing Aid feature wherever they go. Their ease of use, portability, and seamless integration with existing Apple devices make AirPods an effective functional aid in certain contexts, particularly for conversations in noisy environments.

In contrast, the charity or tragedy model frames disability through narratives of pity, dependency, or external intervention. Apple’s design approach notably avoids this framing. AirPods are not marketed as devices for “helping” people with hearing loss, nor are users positioned as recipients of care. Instead, assistive features are embedded into a desirable consumer product, reducing stigma and avoiding the portrayal of disability as a tragic condition requiring sympathy.

Conclusion

When compared with traditional assistive hearing devices, the distinction becomes clearer. AirPods, even with OTC hearing aid functionality, lack a level of clinical personalization and are not intended to replace prescription hearing aids for users with moderate to severe impairments. Instead, they function best as a supplemental or situational assistive tool. Additionally, despite being more affordable than traditional hearing aids, the cost of AirPods can still present a financial barrier, highlighting how accessibility in consumer technology often remains tied to affordability.

Apple AirPods represent a significant shift in how assistive technology can be designed and perceived. Through the medical and functional models, they act as a compensatory solution, through the charity model, they resist pity-based narratives and through the social model, they reveal progress in accessibility. While AirPods should not be viewed as replacements for traditional hearing aids, they offer a compelling example of how inclusive design in mainstream products can expand access and challenge conventional understandings of disability.